What to leave in, what to leave out. Writing is not just all we remember. It is choice.

Now I find myself pressed to do the very same—choose, in telling you about the Lydia Davis event that took place at Purchase College just yesterday.

Does it matter that, before and after the event, I met one of the nicest library staffs you’d ever want to meet? Or that Joe Swatski, reference librarian, wrote the kindest introduction filled with wit and dreams and correspondence-turned-art, that would mirror Davis’s own devices in the hour that followed? What about the edamame that Andrew and Eileen (two library staff) discussed with me (though we judged it, initially, to be an unmatched cucumber dip). The blue cheese, the Swiss, the honey jar (honey!), even a small spread of caviar near dried apricots and cranberries on a pedestal of green marble. The hummus (oh, the hummus). Or my daughter dancing through the art stacks, to Bach—the music so lovingly picked by the staff, because they discovered that Bach was a Davis favorite. What if Susanne hadn’t smiled so winningly? (I was only dropping in to the library for a moment, and she invited me to stay and cover the event. Clearly, I was convinced. And that was before I discovered the pita chips drizzled with olive oil, and the roasted garlic tucked into the dips).

“Hi, I’m Nancy.” Davis recalled this simplest of statements, overheard. Why tell us? Why include? For Davis, who often listens in, it’s partly about language, heard. Language, emphasized by a particular tone or gesture. As she would later reveal about a Norwegian writer who writes about the most mundane things, a writer she loves not for the common but for what he mines from it in tone and description and depth of thought, she does not shy from the banal. It’s about what you do with it as a writer.

And Davis does a lot.

In a letter of complaint to a pea company, Davis made me laugh.

“I tell writers they should translate at least one work, ” she shared with a career-hopeful student after the event. Yes, Davis is a translator. Translating Proust drove her to challenge herself to write the shortest “stories” she could write. Clips of language, Twitter length and less, that would still have meaning.

Her works, her writing life, lauded with accolades (MacArthur Genius Fellowship, Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French government, finalist for the 2007 National Book Award, Man Booker International Prize, to name a few), blur the lines between poetry and prose, both in their style (compressed) and their length (sometimes a single line like so: “Under all this dirt, the floor is really very clean.”)

I thought of my other daughter, who is known for her penchant for writing preludes, first lines, single chapters of stories she will surely never finish. What makes an ending? Of a story, a sentence? What makes a poem? What makes prose? These are questions Lydia Davis’s work surely raises.

The Cows was sitting on the table. I bought it—for sentimental reasons formed that very day. I had taken Prelude Daughter to a local coffee shop just hours earlier. A place called The Black Cow, where she took the most enchanting photographs and I learned that coffee beans are white seeds we roast to brown perfection. How had I missed this detail all my life, when the coffee cans always declare a roast!? It comes to what we see and don’t see.

Lydia Davis sees things with a keen eye. She sees the way she hears. An old woman tussle—her mother’s and a friend’s (Jane’s)—over a cane becomes a humorous walk back and forth, with and without canes, with the wrong one and then the right one and then the wrong one, all set in Dick and Jane style language. You have to laugh. (I did. Davis was hilarious in ways that much of the young audience in the center of the room seemed not to quite get, yet.)

But how could you not laugh at the peas? I laughed even harder at those, vaguely regretting the distinctive quality of my laugh. In a Letter of Complaint to a pea company, Davis made me laugh. I fault her for it, due to the description of a poorly colored pea on a frozen peas package, that made the peas look less appealing than they probably should. She wrote the letter to save the company, so she says. It’s not clear if it worked (she sent a less extreme version to the pea purveyors and kept this one for publishing). Her final line of the letter could even be a plea to all writers of yellow, mealy prose: “Please reconsider your art.”

To this, another Davis Letter of Complaint addressed the need to reconsider your terms. “Cremains, ” she complained to the funeral parlor that handled her father’s death, “sounds like a milk substitute… or a chipped beef dish.” The representative could simply have used ashes, she counseled. It’s old. It’s in the bible, after all. “We would not misunderstand ashes.”

That funeral representative, it seems, could have also used Davis’s advice on writing your dreams. “Don’t tell a dream straight.” Select, she advises. Shape. Such shaping begins at the micro level, with even a single word that can make or break a sentence (or a mourner’s heart). Davis lives by her own rules. And the results are, by turns, incisive and addictive.

Now, there are things I haven’t told you about the evening. (Sausages, salamis, a fly traveling illegally on a bus to Boston, Oh Shakespeare!). For those uncommon common tales, you’ll have to read Davis. Or find her at Purchase College if she ever returns—minus milk, plus honey (and if we are lucky, hummus, oh hummus).

Lydia Davis is the author of seven collections of stories, a novel, poetry chapbooks, and numerous essays. Her work has also been widely anthologized. She is a professor of creative writing at SUNY Albany. Photo by Martin, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by L.L. Barkat, author of Rumors of Water: Thoughts on Creativity & Writing.

_______________________

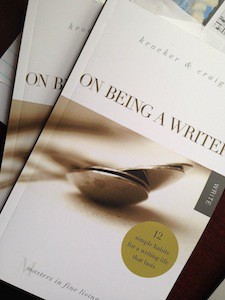

Is your writing life all it can be?

Let this book act as your personal coach, to explore the writing life you already have and the writing life you wish for, and close the gap between the two.

- Poetry Prompt: In the Wild Secret Place - January 6, 2025

- Journeys: What We Hold in Common - November 4, 2024

- Poetry Prompt: My Poem is an Oasis - August 26, 2024

Laura Brown says

I love, love, love her work. Glad you stopped into the library for a moment.

L. L. Barkat says

Where did you first learn of her? This was a fine introduction for me, getting to hear the words given shape with her own voice.

Laura Brown says

You know, I was trying to remember that when I made that first comment. Let’s see — it must have been the 2001 Best American Poetry anthology, which has her piece “A Mown Lawn.” I probably Googled her, looking for more, and came across this interview with Francine Prose.

http://bombmagazine.org/article/2086/lydia-davis

Maybe 8 or 10 years ago I found “Break It Down” and “Almost No Memory” in a wonderful used bookstore in Fayetteville. I’ve read most of her books since, except the newest, “Can’t and Won’t,” and the cows book. She writes like nobody else. And yes, the very subtle humor is part of the draw for me. I think she’s hilarious, but I would guess conservative with her laughs in public.

L. L. Barkat says

I thought she was hilarious too. I’ll have to read some of the poetry. (The cows are mystifying me so far. We’ll see 🙂 ).

Laura Brown says

The things she’s had in the Best American anthologies are there because someone considered them prose poems. Her work is hard to classify.

If you have 27 minutes to spend, here she is out reading in a field and discussing the cows book.

http://channel.louisiana.dk/video/lydia-davis-all-i-get-out-three-cows

L. L. Barkat says

I didn’t have 27 minutes to spend. Yet. But I did read more of the cows last night in between reading my girl’s World History text to her (I read during the interim moments when she was answering the questions, before we had to move on to the next section). Kind of… a grazing approach 😉

Maureen says

Beautifully written, as always.

L. L. Barkat says

Thanks, Maureen. This writing was an early morning effort. The light was not yet making its way over the hill, and I heated just some leftover tea for company. 🙂