Hamlet—Sane or Insane? That Is the Question

In Shakespeare’s classic tragedy of intrigue and ghostly mystery, some have asked, “Was Hamlet sane or insane?” The answer depends partly on how you define insanity and at what juncture of the play you’re making your judgments.

When the play begins, Hamlet is going through a rough time, and it just gets worse with the introduction of a vengeful ghost who wants to use Hamlet to carry out his plan of retribution. At this stage of the play, there is no sensible “plot” reason for Hamlet to pretend to be insane. Yes, he has his justifications, but it is entirely unnecessary and calls more attention to him than if he’d just carried on like he had been and then quietly murdered the king.

On the other hand, Hamlet has felt forgotten and conflicted from the start, in a setting where he can’t really do anything about it, and he doesn’t sense he has anyone to turn to, and he feels like he has to hold it together. If he pretends to be insane, he doesn’t have to hold it together for people in his immediate circle or for larger society. It’s a way to let go of all his bitterness and anger and desperation, and its also a way to call attention to himself, to ask for help in a way that none of his previous actions had managed to do.

But help from whom? He won’t accept it from his mother, his uncle is a murderer, his father’s ghost is interested in nothing but revenge, and in this mix of isolation and paranoia he starts to suspect even his friends, and the smallest “betrayal” becomes inexcusable. When Guildenstern and Rozencrantz check in on him on the advice of the king and queen, that small matter takes on a terrible significance; and furthermore, though they may try to help him, they have no idea and no understanding of his situation, which he plays up, deliberately making them more and more confused and alienating them from him, because he’s angry.

Likewise, he feels he can’t share with Ophelia. Note his reaction to her after he’s first seen the ghost—rushing into her room wildly to tell her what’s happened and seek comfort, and yet drawing away when he realizes he’s alone in this, constrained by the ghost’s path that has been set out for him. Their relationship then goes downhill; when she betrays him by conspiring with her father, he lashes out at her bitterly.

The only person who isn’t affected by this pattern of events is Horatio, who bears the dubious honor of never “betraying” Hamlet, even when his schemes have gone so far that he calmly admits to have sent his former friends to their death (justified, of course, he thinks, because the letter they were carrying said to murder him–even if they didn’t know the contents of the letter).

Hamlet is most likely never “mad” in the way he pretends to be, but he uses the pretense of madness to speak–sometimes in coded, riddling, circumspect ways, other times quite plainly but without the context that would explain it–of the very real burdens he’s labouring under; and the truth is that he does deteriorate over the play as the strain of having to murder his uncle on the advice of a ghost he’s not sure he should even trust (something which of course necessitates secrecy) added to a break-up with his girlfriend and what seem, under the circumstances, to be betrayal after betrayal by everyone he trusted, begins to degrade his sanity.

Though Hamlet perhaps had no predisposition to mental illness, he certainly wasn’t in any way in a mentally healthy place by the end of the play, when he was so stripped down from the young man he used to be that his only purpose in life was to finally kill his uncle and then die. And no, he didn’t plan to die, but he was prepared for it, unconsciously he had been preparing for it from the moment the ghost gave his task, and all that lay in between was to cut ties before he left.

Hamlet knows that when he kills his uncle, it will all be over one way or another. He will be unravelled, his part will be finished. When he reaches the cold certainty at the end of the play, when, even against Horatio’s insistence that the duel with Laertes is a bad idea, he goes forward anyway, even agreeing it may very well be, it is not a triumph. He has reached rock bottom, and has nothing left. Call it madness if you will. Love and affection keep us sane, and the sane seek to preserve them. By the end of the play he is completely unmoored from such livening ties, through actions of his own and pressures from the outside world.

Photo by PsLee, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Sara Barkat.

Click to get FREE 5-Prompt Mini-Series

Browse more Shakespeare Resources

Read Romeo and Juliet Character Analysis

How to Write a Shakespeare Sonnet

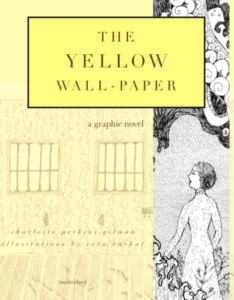

“Sara’s stunning, heartbreaking, and relevant illustrations help to tell a difficult, haunting story. I will return to the story, as I do with all those stories I love, again and again.”

—Callie Feyen, teacher

- Good News—It’s Okay to Write a Plot Without Conflict - December 8, 2022

- Can a Machine Write Better Than You?—5 Best (And Worst) AI Poem Generators - September 26, 2022

- What to Eat With Dracula: Paprika Hendl - May 17, 2022

L.L. Barkat says

Sara, I love this. It also makes me think that depending on culture and time period sanity might be defined differently.

There was certainly a cleverness to his “madness,” but just because we seem to be in control of our madness doesn’t mean we aren’t mad. Social indicators are certainly helpful. The one who withdraws permanently, cuts ties altogether, might well be mad. Or maybe if the culture around that person is mad, withdrawal might be the sanest thing to do.

You got me thinking!

L.L. Barkat says

And I also meant to say… let’s talk about that ghost. Is there a reason he shouldn’t trust the ghost? I mean, it’s his father’s ghost, yes?

Callie Feyen says

Sara, I love your Shakespeare essays at Tweetspeak. I learn so much from you. If you ever find yourself having a hankering to teach, my classroom is always open. 🙂