Poet and author Jake Adam York had published three collections of poetry when he died of a stroke in 2012 at age 40. He had a profound interest in social history, and his poetry was focused on the history of the civil rights movement. Specifically, he was writing to remember, and to memorialize, the 126 people who died between 1954 and 1968 in the struggle for equal rights for Black Americans.

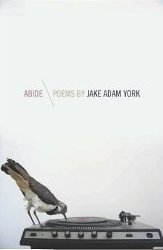

His last volume of poems, Abide, was published posthumously in 2014. It’s one of the five finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry.

I began reading Abide without looking at the poet’s biography, previous works, or articles about him (this is how I do most reviews–starting simply with the work at hand and considering it on its own merits).

I began reading Abide without looking at the poet’s biography, previous works, or articles about him (this is how I do most reviews–starting simply with the work at hand and considering it on its own merits).

I had a number of surprises.

First, many of the poems read like spirituals. Once I realized what the poet was doing, this became less of surprise, and more of an expectation.

Second, the names and experiences York recounts and memorializes are the names and experiences my childhood. I grew up in New Orleans, and I recall the newspaper and television coverage of the civil rights movement, and the violence which often resulted. For someone even remotely familiar with what happened, the poems take on a sense of immediacy, and a news-like quality.

The third surprise was discovering that York was not a Black American. The poems are not those of a detached observer or even a sympathetic historian of the civil rights movement. York wasn’t even born until after the main wave of civil rights protests was ebbing after the 1960s. (If I had to pick a date when the movement crested, it would be 1968, with the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy.)

No, these are the poems of a man who identified with those who died as much as he kept trying to understand the people and the events. The repetition of several of the titles suggest that these were conversations York kept having and was not likely to complete, even as each one took him more deeply into what happened.

And then there is the sheer beauty of the poems themselves, each incorporating a longing, a desire to make meaningful lives that were tragically and stupidly cut short by hatred and fear, like this poem, “Mayflower, ” in which “a young man’s voice / becomes a young man’s / silence.”

Mayflower

For John Earl Reese, a sixteen-year-old, shot by Klansmen through the window of a café in Mayflower, Texas, where he was dancing, Oct. 22, 1955

you hear its quiet

which becomes part of the song

and lives on after,

struck notes bright

in silence

as the room’s damp—

wallpaper and wall

muffling the high cicadas’

whine, mumbling

talk from another room—

hangs like the thought

of a roof in the midst of rain

long after the joists

have been brought down.

So the quiet

syllables crowded

full throats once the talkers

have gone away,

and a young man’s voice

becomes a young man’s

silence, all

he did not say

which nothing keeps

saying in the empty room

between the pines

that hold the quiet

of the song he cannot sing

the sound of a room

without sound

in the middle of what

anyone can hear.

“Mayflower’ is one of three poems in the volume addressing the particular death, creating a kind of ongoing conversation between the poet and the reader, and the poet and the subject. This is a common device that York uses in this volume. The conversation is not finished.

I could use all of the usual words – moving, wondrous, amazing, sobering – but the words fall short. I was reading a piece of my own history here, and Abide is one of those works that seem to change everything. These poems are like questions asked by a child, questions like, “What happened?” Questions like “Why?”

The winners of the National Book Critics Circle Awards will be announced on March 12. For the next few weeks, we’ll be featuring the five nominated works in the poetry category. Last year, the 2013 winner for poetry was Frank Bidart’s Metaphysical Dog, which we reviewed here in August, 2013. Next week, we’ll look at Christian Wiman’s Once in the West.

Photo by ClaireBurge, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Elizabeth Torres Evans says

This article resonates with me since I recently attended a poetry presentation by the Chapel Hill historical Society regarding the poet George Moses Horton who had been a slave over 60 of his 80 odd years.

Maureen Doallas says

I have all of York’s work and have re-read him numerous times. He was, without question, one of America’s finest poets, and his death at so young an age was heart-breaking.

There is now a poetry prize named after him.