For the first 31 years of my life, the closest I ever came to the Great Plains was 37, 000 feet above, as I flew over the patchwork of fields and farms toward my final destination. When I moved from New England to Nebraska nearly fourteen years ago, my expectations of what I’d find were based entirely on stereotypes: the easy-going Midwesterner—corn-fed, robust, salt of the earth; combines slicing through a sea of grain; acres of cornstalks whispering in the breeze. I envisioned myself as an aproned Meryl Streep straight out of the Bridges of Madison County, setting a piping hot apple pie on the porch rail.

As it turned out, my expectations couldn’t have been farther from reality. Nebraska, with its wide sky, stark landscape and relentless winds, was not what I had imagined at all. For a long time, I couldn’t quite figure out where I fit amid all the space.

I was recently reminded of my early days in Nebraska and that vast chasm between my expectations and reality when I visited the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha. Although the museum is home to more than 11, 000 works, including Renaissance and Baroque masterworks by Titian, El Greco and Veronese; Impressionist masterpieces by Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir, and Claude Monet; towering blown glass sculptures by Dale Chihuly, and even a recently restored Rembrandt, it was the pieces that captured the people and places of the Midwest and the West that most captivated me.

As my husband and I strolled into one of the galleries, I laughed when I caught a glimpse of one of the most celebrated paintings in the Joslyn collection: Grant Wood’s Stone City, Iowa.

“This is a bit how I imagined Nebraska before we moved here, ” I said to Brad, pointing at the Seussian trees, quaint steeple and Rubenesque hills.

Wood’s idyllic rendering of the small-town rural America was intentional, offering a comforting pastoral ideal to a nation struggling through the Great Depression. But as I gazed at the painting, I wondered if idealized portrayals like Wood’s had, at least in part, informed my fantastical notion of the Midwest. Stone City, Iowa stood in sharp contrast to the landscape I had captured with my point-and-shoot camera not long after I first arrived in Nebraska.

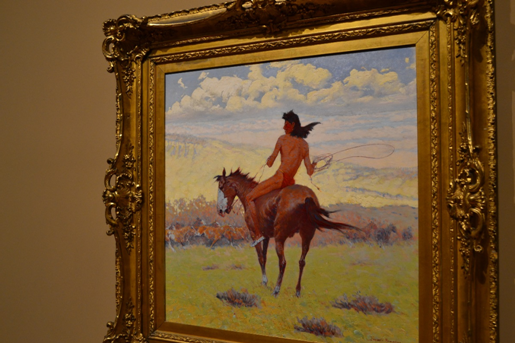

As I strolled through a gallery featuring the Joslyn’s internationally recognized collection of artworks depicting the American West, I pondered the artist’s power to shape and influence a viewer’s understanding of a particular place or people. I was struck, for instance, by romanticized depictions of both the landscape and the Native American people by artists including Frederic Remington, N.C. Wyeth and Eanger Irving Couse.

“Painters created an image of the West as a rough-hewn paradise of rugged landscapes and daring action, ” the gallery text explained. “This vision—equal parts fact, myth and nostalgia—continues to stalk us in movies, advertisements and in our own imaginations, even as we acknowledge the complexity and contradictions of the West.”

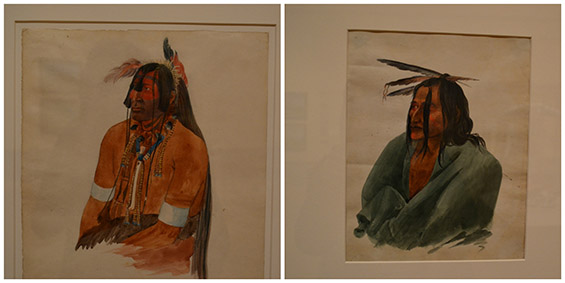

A few steps away in an adjacent gallery, I stopped in front of a selection of formal portraits depicting Native Americans. The accompanying signage explained that these paintings were among hundreds produced over three decades, beginning in the 1820s, when Plains Indians were brought to Washington D.C. on diplomatic missions. Thomas L. McKenney, superintendent of Indian Affairs, commissioned artists to paint portraits of the visiting chiefs with an eye toward creating a National Indian Gallery.

The gallery was never constructed, but it’s worth considering the impact of these portraits, not only on the white men and women who viewed them, but on the Native Americans who sat for the artists as well. One can’t help but notice the Anglicized features of the Native Americans portrayed in these commissioned paintings, especially as compared to the sketches by Swiss artist Karl Bodmer displayed on the opposite end of the gallery.

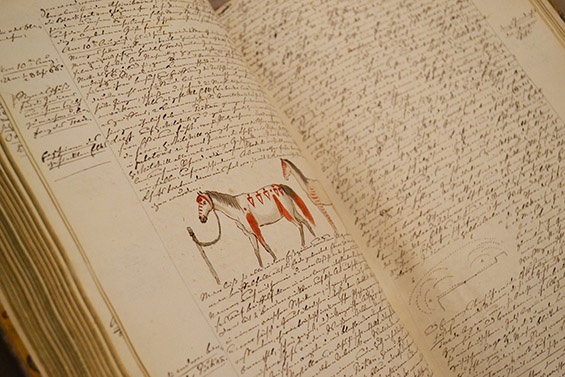

The Joslyn is home to the largest collection of works by Bodmer, who was hired in 1832 by the German explorer and naturalist Prince Maximilian Wied-Neuwied to document his expedition to the American West. The two traveled 2, 500 miles by steam- and keelboat up the Missouri River as far as present-day Montana. They wintered at Fort Clark, near the Mandan villages, and then continued downriver in the spring. Bodmer’s portraits were the first accurate portrayals of western Native Americans in their own environment. Maximilian’s three volumes of journals, which were published in 2008, 2009 and 2001, along with his collection of 350 of Bodmer’s watercolors and drawings, are the centerpiece of the Joslyn collection.

Although Bodmer’s watercolors and sketches were not hung directly next to the portraits that had been commissioned by the federal government, the contrast was obvious. One exhibit of paintings depicted the Native Americans as the white men preferred to see them (or the way the white men preferred they be seen by viewers); the other as they actually were.

On the hour-long drive home from Omaha to Lincoln, I gazed out the window at the shorn fields unfurling along I-80. Nebraska’s barren landscape wasn’t what I had expected when I first moved here almost fifteen years ago. The vast land and the seemingly endless sky were unfamiliar and unsettling to me. Over time, though, I’ve found beauty in the spaciousness of this place. There’s room to breathe here and a quiet slowness I didn’t anticipate. So much of what I’ve come to love about Nebraska I discovered simply by living in its landscape.

Browse more Literary Tours

Browse more Art Galleries and Exhibits

Featured photo by USFWS Mountain Prairie, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post and photos by Michelle DeRusha.

___________________

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Regional Tour: Homestead National Monument, Beatrice, Nebraska - November 13, 2015

- Making Little Free Library No. 25, 001 - November 4, 2015

- Regional Tour: North House Folk School, Grand Marais, Minnesota - August 12, 2015

L. L. Barkat says

Various thoughts…

how much of landscape do we fashion and how much of it fashions us (and how we see)?

what makes a painting idyllic? (I’mnoting the fat hills, for instance)

what is the function of art in time of distress—both making it and viewing it?

Thanks for giving me a bit to ponder this morning 🙂

Laura Brown says

I love that first question. Makes me think of when I was in grad school, riding with a classmate to Michigan for a holiday weekend. “Don’t you love how the land flattens out?” she said as we drove across northern Ohio. And I said something like no, it made me feel exposed when the hills start to go away. Each of us was surprised, maybe even incredulous, that the other felt that way.

That doesn’t really answer your question, though.

Michelle DeRusha says

I absolutely felt claustrophobic, strangely, when I first moved to the midwest. I felt like the sky was pressing down on me – it was just too much. Now when I go “home,” back to New England, I tend to feel like the trees are pressing in on me. It’s all what you are accustomed to, I guess.

Maureen Doallas says

The Washington Post on Jan. 25 had a feature on a huge fire at the Smithsonian here in D.C. in 1865. More than 250 original portraits of Native Americans by two painters were destroyed along with Smithson’s personal papers. It was an incredible loss to America.

I find the Wyeth illustration so strange, even more so as an ad.

L.L. raises some wonderful questions, which, I think, apply equally well to discussions of poets and their work.

Good piece, Michelle; thank you.

Sandra Heska King says

Is it even possible to depict life accurately or is it always colored by the creator? Or maybe it can only be done through a blend of our creations–whether by word or brush or music…

Love tagging along on your dates, Michelle.

Megan Willome says

So good, Michelle! I’m as struck between the contrast between the painting of Iowa and your camera shot as the contrasting paintings of Native Americans. Finding beauty in the way things actually are rather than how we might like them to be or how we thought they were. This piece makes me want to pay attention.

Michelle DeRusha says

Yes! Honestly that was a hard lesson for me to learn about Nebraska. For the longest time I wanted it to resemble what I had envisioned. It wasn’t until I put the stereotypes (and hopes) aside and really looked at what was actually here that I was able to see that it’s beautiful, very beautiful, in its own stark way.

Will Willingham says

Was really struck by the contrast in the Native American paintings, not that it was surprising so much, but just seeing it there, side by side as it were. Seems to be a reminder of the pitfalls that await us when we attempt to tell another’s story — by art or by words. And by that I don’t mean one shouldn’t try to tell the stories of another, but I think we have our inevitable biases and filters and angles, and am thinking on what must be done to ensure we can bypass those and tell the story that needs to be told.

Who knew your little trip to Omaha would raise such great questions as this piece seems to have.

Thanks, Michelle. 🙂

Michelle DeRusha says

Ooooooh, really good point about the perils of attempting to tell another person’s story. It’s a real challenge, I think, not to let those biases creep in. That’s why I like to write memoir/personal narrative – since it’s my story, I can tell it any which way I want. 🙂

Diana Trautwein says

Oh, Michelle! I love this piece! So thoughtful, on multiple levels. And the discussion about landscape reminds me of when I took my two daughters on a college-dreaming trip when they were in high school. We made a circle of most of the UC campuses and when we turned inland after seeing Berkeley and headed toward Davis, my eldest said from the backseat: “I could never go to school here. I feel unrooted, like I’m drifting.” Davis is completely flat, with no hills in sight. Our kids grew up in the foothills of the San Gabriel mountains and went to multiple camp experiences at higher elevations. They were used to feeling secure with ‘big’ landscape around them. Flat stuff? Not so much. It is very much what we get used to, I think. And then learning to love what we find around us when we’re forced out of our usual habitat.