After wrangling for a lunch-hour parking spot in downtown Lincoln, Nebraska, I arrived at the Sheldon Museum of Art and was tempted to lie down next to the errant head tipped sideways on the front steps. Despite his furrowed brow, the head seemed markedly more relaxed than I. My angst dissipated, though, the moment I spun through the revolving door and stepped into the Sheldon’s atrium, with its floor-to-ceiling windows, pristine marble floors and uncluttered spaciousness.

The Sheldon Museum of Art is located on the campus of the University of Nebraska and houses more than 12, 000 works of art in all media, only a fraction of which is displayed at any one time. The collection of American art includes 19th-century landscape and still life, American Impressionism, early Modernism, geometric abstraction, Abstract Expressionism, pop, minimalism and contemporary art, plus a sculpture garden with 30 large-scale pieces displayed year-round.

In the thirteen years I’ve lived in Lincoln, I’ve visited the Sheldon just once. I remember shuffling from gallery to gallery in a sleep-deprived haze, my infant son strapped into a carrier on my chest.

Thirteen years later, my second visit took place on an unseasonably warm afternoon in the middle of finals week, just two weeks before Christmas. I had the museum to myself. When the glass gallery door shut behind me with a quiet click, I stood in the middle of the room and exhaled. The space was silent, save the Christmas music that trickled under the door from the lobby.

The gallery featured Dialogues, a special exhibition displaying pairings of disparate pieces – “conversation starters, ” the signage explained, that “invite viewers to reflect upon the power of juxtaposition and its role in contemporary culture.”

At first glance, the subject matter of the two horizontal depictions of the Nebraska prairie displayed side-by-side looked similar, but a closer inspection revealed subtle differences. I was surprised to see that the piece on the left, Horizontal Prairie #1, by Francisco Souto, was created in 2014. The gray, bleak landscape conveyed an older, historic feel to me, especially compared to its more colorful companion, an untitled pigment print created in 2009 by Jan Christensen.

On the opposite side of the room, I stood for a long time in front of Cadmium Yellow, Naphtol Red and Ultramarine Blue in 1/1, by Iranian artist Hadieh Shafie. When the piece first caught my eye, I’d assumed the colorful circles were buttons, but the plaque informed me the design was comprised of thousands of hand-dyed strips of paper rolled into scrolls standing vertically on end. The individual papers were each hand-written and printed in Farsi with the word “eshghe, ” which means “love” or “passion, ” a word chosen by the artist because it encompasses her “longing and search for acceptance and understanding.”

Upstairs, the special exhibition Things That Speak: Storied Objects from Lincoln’s Collections showcased objects – many of them utilitarian pieces from everyday life, like a black silk scarf or an old-fashioned car horn – alongside a slice of their story.

“Objects shape our existence, ” the signage explained. “Every day we use or interact with things that relate to the practical, spiritual, emotional or social aspects of our lives. An object often has its own unique history; while it’s usually judged by outward appearance, its significance is increased once the story associated with it is told.”

I learned, for instance, that the scarf, on loan from Lincoln’s Germans from Russia Museum, was typically worn by women as a head covering in church. It was owned by Anna Miller Gruenwald, who died in 1907 en route from Russia to the United States. The exhibit sign didn’t note the cause of death–only that Gruenwald was buried in a Russian village before her family continued their journey. I found myself curious about the rest of her story. How old was she when she died? Why was the German family traveling from Russia to America? Were they fleeing persecution? Dreaming of more opportunities and a better life?

The mystery will remain. A Google search conducted later that evening turned up nothing on Anna Miller Gruenwald.

I also learned that the brass boa constrictor horn, on loan from Lincoln’s Museum of American Speed, was not a child’s toy, as I’d first assumed, but a 1908 automobile horn–an “aftermarket accessory” that was often purchased by car owners to embellish fancier models. As I stood in front of the glass case, I wondered what kind of man would purchase such an ornament. I imagined him a whippersnapper in a crisp pin-striped suit and a straw bowler. Perhaps he carried an ivory walking stick. Certainly he ambled with a bit of a swagger.

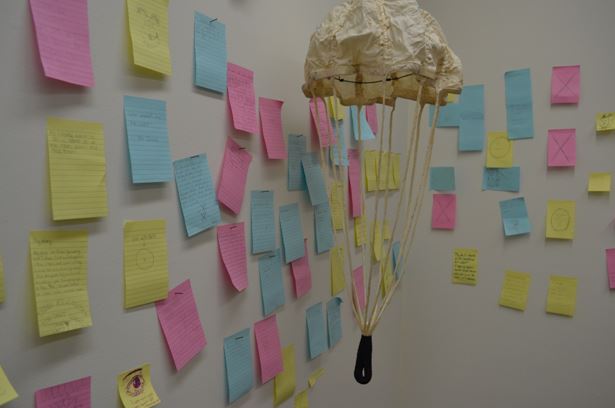

In a small room adjacent to the “Things that Speak” exhibit, I happened upon an art exhibit in its own right: a collection of short stories, poems and ponderings, penned by visitors onto fluorescent Post-It notes and affixed to the walls. “Write your own story about one of the objects in this room or displayed in the exhibit, ” the signage urged. I didn’t scribble a story, but I did enjoy the musings of others, including an anonymous poem about the dilapidated parachute suspended in the corner:

The chute

a blown-open pair

of bloomers

a hope-chest rumpled

bonnet unfurled

a tired old

jellyfish

praying

With time to spare before I picked up my kids from school, I fed my parking meter another two quarters and walked south two blocks to the Starbucks on the corner. I’m glad I did, because on the way, I spotted Claes Oldenburg’s and Coosje van Bruggen’s monumental Torn Notebook. I’d glimpsed the sculpture dozens of times from my car, but I hadn’t ever had the opportunity to view it up close.

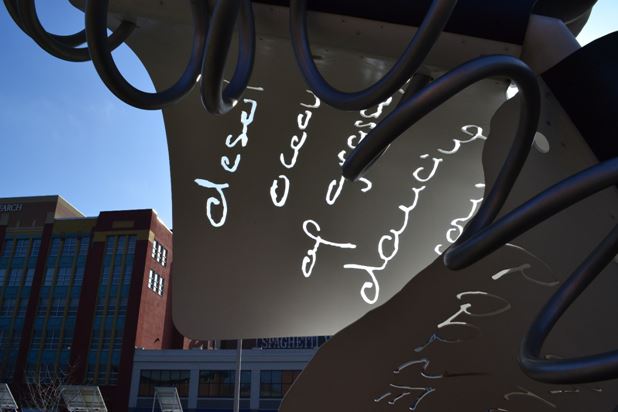

The stainless steel, steel and aluminum sculpture dominates the landscape and offers a startling juxtaposition with the traditional brick buildings in the background. Loose page fragments blow across the grass, while the spiral binding, according to one mini-documentary about the piece, resembles “a tornado, spinning across the plains.”

To prepare for the commission, Oldenburg and his wife Coosje van Bruggen drove from Kansas City, Missouri, through the Missouri River Valley to Lincoln, along the way jotting down their observations of the landscape and surroundings in a notebook. Coosje noted lyrical phrases, like “falcons atop flagpoles, ” “fields of corn–one ear per stalk–in wayward winds swing, ” “crows on the butte” and “buffalo peas, ” while Claes wrote down names of things, including “barbed wire, ” “goose, ” “hoop” and “roller skate.” “Roller skate” was puzzling, until I read that Claes and Coosje had stopped by the National Museum of Roller Skating during one of their visits to town. (Perhaps fodder for another Lincoln, Nebraska, Literary Tour?)

“Only when we were back in the studio in New York, ” Oldenburg wrote in his artist statement, “did we realize that a sculpture about the process of collecting observations could be the perfect subject for a university site.” Coosje’s words fill the top half of the sculpted pages, while Claes’ are scrawled on the bottom. The words are water-cut through the metal, in reverse relation to each other, so that one set of script is always read backward.

I stood for a while on the grassy hillock, snapping pictures of the sculpture from various angles and admiring the way the sun filtered through the looping script. Finally I continued on toward Starbucks. As I walked, I noticed the wind had picked up, as it often does in Nebraska in the late afternoon. It pushed at my back, hastening my steps, and I imagined myself a page torn from a notebook, cartwheeling across the Great Plains.

Post and photos by Michelle DeRusha.

Browse more Literary Tours

Browse more Art Galleries and Exhibits

____________________

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Regional Tour: Homestead National Monument, Beatrice, Nebraska - November 13, 2015

- Making Little Free Library No. 25, 001 - November 4, 2015

- Regional Tour: North House Folk School, Grand Marais, Minnesota - August 12, 2015

Patricia @ Pollywog Creek says

As much as I’ve come to love my rural lifestyle and the art of nature, I do miss the opportunities to engage in culture’s artistic displays. So, thank you, Michelle, for letting me walk with you through the Sheldon Museum of Art and cartwheel “across the Great Plains” on the way to Starbucks. (BTW, I would have ordered a venti cinnamon dolce latte, no whip.)

Michelle DeRusha says

Thanks, Patricia. I am ashamed to admit that I rarely take advantage of the cultural offerings of my city – I plan to change that this year. My hours at the Sheldon were so refreshing – I realized immediately how important it is as a writer and a person to infuse my life with art and culture.

{making note of your drink preference, should I ever happen to be sitting across a table from you in Starbucks, Patricia – a girl can dream, right?}

L. L. Barkat says

Oooo, love the black scarf. So intricate.

And I love the combination of observation and imagination in this piece. Feels to me like a writing excursion as much as an art excursion 🙂

Michelle DeRusha says

I had a major epiphany about “feeding my writing” while I was at the Sheldon, LL – spent some time think about what Ann and Charity said about that in “On Being a Writer,” too. A very fruitful experience!

Will Willingham says

I love that head. I could have just seen that and called it a day. 😉 But there are really some wonderful pieces inside.

Maybe one day you’ll go back and add your sticky note story about the cartwheels and torn pages. 😉

Michelle DeRusha says

Yeah, I had a moment with the head. We bonded. 🙂

Maureen Doallas says

Great tour of some wonderful art – contemporary, conceptual, and more, Michelle. Art feeds me in so many ways; it’s one reason I live in the D.C. area and love visiting NYC.

Charity Singleton Craig says

I love your collection of observations, Michelle. What a wonderful visit, hopefully the second of many.

Like you, I don’t take in the cultural exhibits in our area enough, but when I do, I like to interact the way you describe here, not seeing everything, but spending some time with a few exhibits. I like the way the exhibits observe me back – or maybe it’s just me observing myself observing them. Either way, it’s always a revelation.

And, so excited to hear you are a new contributing writer! Welcome and congratulations.

SimplyDarlene says

Howdy Michelle! Hmmm. I cannot get over that head. While Will liked it, it’s a willy-giver for me. 🙂

My husband’s kin homesteaded in NB; though long-since farmed, the original tract of land remains in the family. And one of the surnames you link is in his lineage. Very small world indeed!

Lynn Morrissey says

Michelle, of all the things you write, your reporting is one of my favorite genres. I have such an appreciation for art, and, I, myself, have spent leisurely hours strolling through museums in St. Louis, my hometown, or those of other cities, including Europe. I think by writing about the beauty you saw likely helped you understand the art better. And in this case, your writing *is* art. Just lovely. And the closing was worth it all.

Fondly,

Lynn

Megan Willome says

This is so nice, Michelle! I’m glad you’re going to be a contributing writer here. Such a good ending, too!

Sandra Heska King says

Squeee with a cartwheel! So good to see you here!

You know, I’ve felt a lot like that head lately. I love how your imagination carried you, and that ending made me smile.

I think it’s time for me to explore some of the cool stuff in these parts. I’ve neglected my artist’s dates and literary tours.