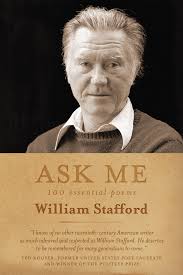

William Stafford (1914-1993) was one of the most distinguished poets of the 20th century. He served as what we know call the U.S. Poet Laureate (then the poetry consultant to the Library of Congress) from 1971 to 1972. He published more than 60 books. His Traveling Through the Dark (1962) won the National Book Award for Poetry. He wrote more than 20, 000 poems in his lifetime.

Stafford’s son Kim, an author in his own right and his father’s literary executor, has assembled a collection of Stafford’s poetry simply entitled Ask Me: 100 Essential Poems. It’s a collection that’s many things at once: an introduction to Stafford’s poetry, a summary of a life of poetry, a collection of poetic gems, and an illustration of the range of a poetic eye, covering everything from fears of the atomic bomb to a description of a local berry festival that is one part history and one part sociology.

Included are several poems related to Native Americans, and they are among the best in this collection (which is saying something, since the collection itself is the best of the best). Here’s “In the Night Desert:”

then numbs the tongue:

Uttered once clear, said—

never that word again.

“Cousin, ” you call, or “Sister” and one

more word that spins

In the dust: a talk-flake

chipped like obsidian.

The girl who hears this flake and

follows you into the dark

Turns at a touch: the night desert

forever behind her back.

Stafford’s poems are simple, and accessible. He uses common language and straightforward construction. As a result, the focus becomes the words rather than a technique, meaning and substance rather than form.

His life spanned several literary movements – the twilight of realism, the birth and triumph of modernism, and post-modernism, along with a few minor variations on movements like the New Formalism. He’s often considered a regional poet because so much of his work is about the western United States, and yet his poetry transcends the regional and it transcends being defined by a movement.

In his introduction to the collection, Kim Stafford tells this story: “He traveled for poetry—sometimes thirty readings in thirty days. He was an ambassador for the possibility of peace through poetry. The calendar was black with engagements. At a reading, following one of his deft, quiet offerings, a listener helplessly spoke aloud, “I could have written that.’ And William Stafford, looking kindly at the speaker, replied, ‘But you didn’t.’ A beat of silence. ‘But you could write your own.’”

Stafford had a voice, a unique voice, and he used it to describe the things he cared about. Ask Me provides a clear window into his voice and his poetry.

Why I Am a Poet

My father’s gravestone said, “I knew it was time.”

Our house was alive. It moved,

it had a song. The singers back home

all stood in rows along the railroad line.

When the wind came along the track

every neighbor sang. In the last

house I followed the wind—it

left the world and went on.

We knew, the wind and I, that space

ahead of us, the world like an empty room.

I looked back where the sky came down.

Some days no train would come.

Some birds didn’t have a song.

—William Stafford

Fortunately for us, William Stafford had a song, and he sang it.

Photo by Donnie Nunley, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

Kelly Chripczuk says

Thank you, Glynn.

Maureen Doallas says

I’ve read this several times, along with Kim Stafford’s book about his father and their relationship. It’s a very comforting collection, and an interesting selection of work by an incredibly prolific poet.

Simply Darlene says

60 books?! All poetry?

As always, thanks for the lesson, sir Glynn.