Perhaps the best introduction to the poetry of Frank O’Hara (1926-1966) is what he himself had to say. In “Personism: A Manifesto, ” O’Hara wrote, “I hate Vachel Lindsay, always have; I don’t even like rhythm, assonance, all that stuff. You just go on your nerve. If someone’s chasing you down the street with a knife you just run, you don’t turn around and shout “Give it up! I was a track star for Mineola Prep.’”

That could easily be an Frank O’Hara poem.

O’Hara was one of the lights of what was called the New York School, a group of writers, artists and musicians that included John Ashberry and often Allen Ginsberg. Several of them knew each other from college (like O’Hara and Ashbery). O’Hara crossed all three of the cultural groups represented – he was a poet, he had originally studied music, and he worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

O’Hara was one of the lights of what was called the New York School, a group of writers, artists and musicians that included John Ashberry and often Allen Ginsberg. Several of them knew each other from college (like O’Hara and Ashbery). O’Hara crossed all three of the cultural groups represented – he was a poet, he had originally studied music, and he worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

At the museum, he had started as a desk clerk selling postcards but worked himself up the hierarchy. He eventually became an assistant curator, which was rather remarkable since he did not have an art degree.

His poetry was influenced by music, particularly jazz; abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Koonig; and surrealism. It was read and sounded like the Beats, and the Beats has a lot in common with the New York School. O’Hara and his poetry fit well in both groups. Here’s an untitled poem from 1957:

The eager note on my door said “Call me,

call when you get in!” so I quickly threw

a few tangerines into my overnight bag,

straightened my eyelids and shoulders, and

headed straight for the door. It was autumn

by the time I got around the corner, oh all

unwilling to be either pertinent or bemused, but

the leaves were brighter than grass on the sidewalk!

Funny, I thought, that the lights are on this late

and the hall door open; still up at this hour, a

champion jai-alai player like himself? Oh fie!

for shame! What a host, so zealous! And he was

there in the hall, flat on a sheet of blood that

ran down the stairs. I did appreciate it. There are few

hosts who so thoroughly prepare to greet a guest

only casually invited, and that several months ago.

The poem reads almost like a diary entry (and critics often said his poetry read that way, or like a newspaper report). But you can feel the speed, the sense of urgency, and, ultimately, once you read the end, the sheer oddity of it. (Imagine it being read aloud, or better still, try reading it aloud.)

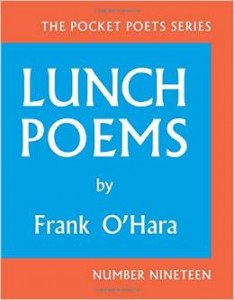

In 1964 Louis Ferlinghetti, owner of City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco (the same publisher of Ginsberg’s Howl), accepted a collection from O’Hara for publication. It was Ferlinghetti who named it Lunch Poems; apparently, O’Hara wrote most of the poems during his lunch hour off from the museum. The collection was finally published in 1964.

While it comes a few years after the height of the Beats, it’s easy to see why Lunch Poems is so much like Beat poetry. The poems are meant to be read aloud. Many seem almost stream of consciousness. Some are funny. Some read like a newspaper report. As small as the volume is (68 pages), it did have a major impact on the course of American poetry. Here’s the untitled poem generally referred to as the “Lana Turner” poem:

I was trotting along and suddenly

it started raining and snowing

and you said it was hailing

but hailing hits you on the head

hard so it was really snowing and

raining and I was in such a hurry

to meet you but the traffic

was acting exactly like the sky

and suddenly I see a headline

LANA TURNER HAS COLLAPSED!

there is no snow in Hollywood

there is no rain in California

I have been to lots of parties

and acted perfectly disgraceful

but I never actually collapsed

oh Lana Turner we love you get up

This isn’t the poetry of academia. This is the poetry of the street (likely Second Street in New York City). It is urgent and topical and somewhat in your face. The poems are gritty, like New York streets.

Two years later, O’Hara was killed in something of a freak incident involving a jeep on the beach at Fire Island. The New York School was there; one of their lights, perhaps their brightest poetic light, had been extinguished.

O’Hara’s reputation grew after his death; friend and fellow poet John Ashbery was a major reason why. O’Hara bridged the Beats and the more contemporary poets, becoming, after his death, a transformation point for American poetry.

This concludes our September series on the Beat poets. On Sept. 2 we had an introduction to the Beats, followed by Jack Kerouac on Sept. 9, Allen Ginsberg on Sept. 16, and Denise Levertov on Sept. 23.

Related:

Poetry Foundation’s article on O’Hara

Frank O’Hara on the web

Poetry volumes include:

Second Avenue: Poems by Frank O’Hara (1960)

Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara (1964)

The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara, edited by John Ashbery and Donald Allen (1995)

Meditations in an Emergency: Poems by Frank O’Hara (1957)

Selected Poems of Frank O’Hara, edited by Mark Ford (2008)

Writings on Art:

Jackson Pollock by Frank O’Hara (1959)

Art Chronicles: 1954-1966 by Frank O’Hara (1991)

Biographies:

City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara by Brad Gooch (1993)

Frank O’Hara: Poet Among Painters by Marjorie Perloff (1996)

Featured photo by Nina Matthews, Creative Commons via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Poets and Poems: Ryan Ruby and “Context Collapse” - February 20, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Jessica Cohn and “Gratitude Diary” - February 18, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Enormous Blue Umbrella” - February 13, 2025

Maureen Doallas says

O’Hara called his work “I do this, I do that” poems. A wholly apt description, I think.

A good biography is Brad Gooch’s “City Poet”.

Martha Orlando says

I was not familiar with O’Hara until you shared here, Glynn. Original, off-the-cuff, and in your face, I’d say. Wonder what he would have accomplished had his life not been so tragically cut short?

Blessings!

Megan Willome says

His poem “Mayakovsky” was on Mad Men.