Perhaps it was the watery eyes of Omar Sharif, the beauty of Julie Christie, the fierceness of Alec Guiness, or the wounded look of Geraldine Chaplin. What it was, I was a young teenager when I was pulled into the movie version of Doctor Zhivago, directed by David Lean. It was one of the movies rarely made today—a big movie with dozens of characters, stories and sub-stories. It was an epic film based on an epic literary work that had only recently been published.

Published in Russian in Italy and forbidden in the author’s own country.

The movie pulled me to the novel by Boris Pasternak, and I read it when I was all of 14. It’s a love story, actually several love stories, set against the backdrop of World War I, the Russian Revolution and Civil War, and the long Soviet night that followed. Pasternak received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958, largely on the strength of Doctor Zhivago and his poetry, but the Soviet regime forced him to refuse the honor.

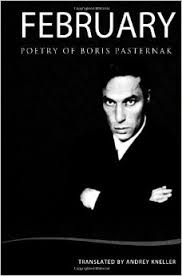

Before he was a novelist, Pasternak (1890 -1960) was a poet. In fact, his prose was not allowed to be published in Soviet Russia, but Russians knew him as a poet, perhaps the leading poet of the Silver Age, the model for poets like Marina Tsvetaeva. His poetry continues to be available; recently poet Andrey Kneller translated a number of Pasternak’s poems and assembled them as the volume February: Poems.

A few were written in the 1910s and 1920s, but most of the poems in the collection date from the 1950s (Pasternak did not publish during the 1930s, and publication after World War II and leading up to Stalin’s death in 1953 was fraught with potential peril). They are poems of daily life and love, of the environment around the poet and the culture he lives in. But the poems are Russia, Russia as it was, is and will be. Here is the poem “Confession”:

Life has suddenly returned again,

Just as once it strangely went away.

On this ancient street, once more I stand,

Just as then, that distant summer day.

Same old people and the same old worry

And the sunset’s fire is still warm,

Just as when the evening in a hurry

Nailed it swiftly to the stable wall.

Women in their old and cheap attire

Wear away their shabby shoes at night.

Afterward upon the roofing iron

By the rooftops they are crucified.

Here is one, so wearied and unwilling,

Up the steps beginning to ascend,

Rises from the basement of the building,

Walks across the courtyard on a slant.

And again, I’m planning my charade,

And again, all’s pointless and dull.

And a neighbor, passing through the gate,

Disappears and leaves us all alone.

If you’d like to see a slightly different translation of the same poem, read the version posted at Poemhunter. The translations are similar but do have some significant differences; I prefer Kneller’s version. Comparing the two provides an idea of how different translators approach the same text.

The volume includes the title poem, “February, ” as well as one written in 1958 entitled “Nobel Prize, ” which offers a glimpse of how Pasternak privately reacted to being forced to turn it down. In all, February includes 29 poems, with the last several poems reflecting the poet’s interest in Christianity, which is also one of the themes of Doctor Zhivago and written about the same time.

I like these poems that seem so Russian, or what we think of as Russian. They have a place, too, in literary history, written by a poet who physically escaped the dangers of living in a tragic country in a tragic time but was profoundly shaped by that same country and time.

Featured photo by Pasko Tomic, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Andrey Kneller says

Thanks for showcasing my work. I’ve translated quite a lot of Russian poetry. If you’d like to read any of my other books, I would only be happy to send you the ebook versions by email.

Would you consider posting a short review of my book on Amazon? As an indie author, it’s really hard to attract much attention, reviews give my work some credibility.

Thanks again,

Best,

Andrey

Glynn says

Andrey – I really enjoyed the poems. Thanks for the comment.

Zachary Garripoli says

Love it! I saw Yevteshenko read in NM years ago, and have been hooked on the Russians. Particularly Mandelstam.

Glynn says

I can remember when Yevtushenko toured the US – way back in the late 1960s or early 1970s. He had something of a “bad boy” reputation.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

Maureen Doallas says

It’s been years since I read Pasternak. What a dramatic cover for ‘February’.

Shraddha Sharma says

I read poem july by Boris Pasternak. But i couldn’t decipher the hidden meaning behind the poem. Was it all about the month july or i am missing something . Please help me understand the meaning of the poem.