Tweetspeak’s virtual Literary Tours take us to destinations of all kinds, finding inspiration in places such as art museums, libraries, and natural settings. Today, we tour a Georgia O’Keeffe exhibit at San Francisco’s DeYoung Museum.

______________________

It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things. – Georgia O’Keeffe

Before I visited the San Francisco DeYoung Museum’s exhibit, Modern Nature: Georgia O’Keeffe and Lake George, I didn’t know how O’Keeffe’s relationship with Alfred Stieglitz and Lake George influenced her artistic development. I was more familiar with her work in New Mexico—a place she saw as her “spiritual home”—which occurred during the second half of her long career, after Stieglitz died.

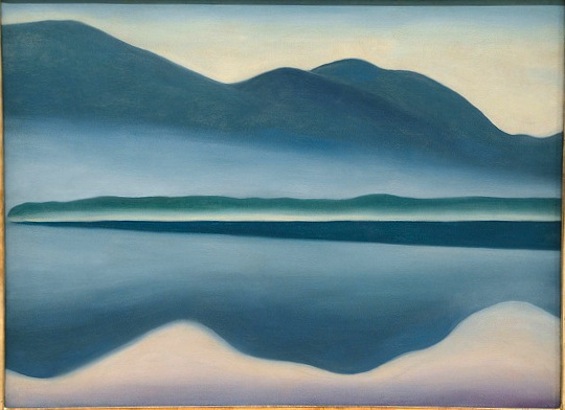

The exhibit highlighted how O’Keeffe found new subject matter at Stieglitz’s bucolic family estate on Lake George, which she visited annually from 1918 until the early 1930s.

Two of her early works painted in greens, blues and white—Series 1, No. 10, 1919 paired with Series-1-No. 10A, 1919—appear to be two different perspectives from a boat looking out over Lake George with a view of trees. The voice in the headphones suggested the wrinkled white folds at the bottom of one of the paintings are Stieglitz’s knees, because O’Keeffe had a “trim” physique.

Storm Cloud, Lake George, 1923 was one of O’Keeffe’s favorites. I’m surprised, because I’m more acquainted with her paintings inspired by the colors and deserts of New Mexico, whereas Storm Cloud is black and charcoal grey. Was Storm Cloud a favorite because of her abstract rendering of the storm, or because it reminded her of being caught in a storm with Stieglitz? Perhaps both?

A Celebration, 1924 depicts billowy white clouds ascending to blue swirls in the canvas’s upper portion. It elicits a feeling of lightness. In 1924, Stieglitz divorced his wife and married O’Keeffe. The audio tour narrator hinted O’Keeffe didn’t necessarily want to marry. A nearby placard stated the “clouds” reveal O’Keeffe’s “inward thoughts and feelings.”

The audio tour and biographical film, shown in a separate room, both suggested O’Keeffe painted to make the intangible, such as her feelings, more tangible.

A rich royal purple petunia and its yellow center dominate almost the entire canvas of Petunias, 1925. O’Keeffe was an innovator because no one before had painted a magnified close-up of a flower. Of her large-scale petunia painting, O’Keeffe wrote: “I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it—I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.” New Yorkers noticed; but sadly, Stieglitz’s 1921 exhibit of nude photos of O’Keeffe overshadowed her exhibit. Stieglitz said he didn’t show O’Keeffe’s face to “preserve her anonymity.”

On one wall, a 1930 series of five paintings (viewed from left to right) of a Jack-in-Pulpit wildflower show O’Keeffe moving from realism to a more abstract style while also focusing in greater detail on the flower’s center or pistil. The last painting in the series is the most abstract: several enfolded curves in bold graphic colors. The voice in the headphones said many in the public saw sexual connotations in her art because they were unable to separate her paintings from Stieglitz’s nude images of her. Years later, O’ Keeffe stated the sexual connotations others saw in her art were not what she saw when she painted her flowers.

O’Keeffe’s words illustrate a risk all artists who share their work must deal with: what another sees in an artist’s work may not be what the artist intended.

Between 1922 and 1931, O’Keeffe painted 34 paintings of autumn leaves; some were exhibited.

Brown and Tan Leaves evokes sadness in me instead of the joie de vivre generated by her flower paintings. A giant, faded beige leaf dominates the center of a large canvas. The giant one is thin and as light as ivory near its stem. An upright medium-sized brown leaf stands to one side of the center leaf, while on its other side, a much smaller green leaf leans against it.

The audio tour suggested Brown and Tan Leaves, 1928 represents Stieglitz’s affair with Dorothy Norman (40 years his junior) and his relationship with his wife, O’Keeffe, 18 years younger than him. Presumably, the oversized beige leaf in the center represents Stieglitz while the medium brown leaf is O’Keeffe and the smallest green leaf symbolizes Norman.

O’Keeffe created another painting, Dark and Lavender Leaves, 1931 as her marriage deteriorated. In the painting, a much smaller oak leaf nestles over a larger dark leaf, which is a little torn on one side. A placard states: “The vibrant lavender leaf appears both protected and overshadowed by the decaying dark leaf.” Was this O’Keeffe’s way of revealing her ambivalent feelings toward her marriage?

The exhibit gave a glimpse into how Lake George’s natural beauty and her relationship with Stieglitz influenced her art, from leaves as fragile as a woman experiencing love and loss, to a stormy lakeside scene as a backdrop for a budding romance and the flowers that inspired her to change how we saw them. True to her vision, O’Keeffe sought to “get at the real meaning of things.”

Featured photo by Ky Dally, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Image of artist by torbakhopper, sourced via Flickr. Image of Lake George painting by Adam Fagen, sourced via Flickr. Image of Petunias painting by rocor, sourced via Flickr. Post by Dolly Lee.

Our virtual Literary Tours take us to literary and artistic destinations of all kinds, including writer’s residences, libraries, museums, galleries, and historical locations.

Browse more Literary Tours

Browse more Galleries & Art Exhibits

______________________

Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter.

We’ll make your Saturdays happy with a regular delivery of the best in poetry and poetic things.

Need a little convincing? Enjoy a free sample.

- Regional Tour: The Getty Center in Los Angeles - November 6, 2015

- Regional Tour: A Glimpse of Yosemite - August 14, 2015

- Literary Tour: Mariposa Museum & History Center - May 20, 2015

Ann Kroeker says

Insight into a fascinating woman, provided by you, Dolly, and O’Keeffe’s own art. Enjoyed seeing the exhibit as a virtual literary tour, through your eyes and description.

Maureen Doallas says

DeYoung’s a lovely museum; it’s been years since I was there.

I tend not to use audio or read wall text when I’m going through a show, particularly if I’m looking at work for the first time. It always interests me to read or hear of curators’ different perspectives on an artist’s work, though I think that sometimes, a flower is just a flower.

Lake George is a gorgeous area. I don’t think O’Keeffe could help but be inspired.

Have you been to the Santa Fe O’Keeffe museum, Dolly? I was last there in 2002 and loved seeing work there that’s not been on view elsewhere.

Dolly@Soulstops says

Thank you, Ann, for coming with me 🙂

SimplyDarlene says

It’s a shocker that prior to 1925 “no one before had painted a magnified close-up of a flower.” The minute details of a thing, whether the flower petal’s edge or the fibers of a paper plate, amaze me.

Dolly, thanks for this bit of lovely today.

Blessings.

Marcy Terwilliger says

My cousin is Debra Fritts, she lives in the area where O’Keeffe last resided. Debra is an amazing artist who not only teaches her talents but her work is in well known Gallery’s in the West. Please goggle her and look at her amazing work. She has a piece at Sundance.

Charity Singleton Craig says

This was wonderful, Dolly. I’ve always loved Georgia O’Keeffe, but you’ve offered new information and a fresh perspective.