Like most Americans of a certain age, I first met Beowulf in a high school English class. I know exactly where I met him—in a classroom on the second floor of the school, in a textbook entitled England in Literature. It was an all-boys high school, so the story of Beowulf, Grendel and Grendel’s mother held our attention more than most works—we couldn’t resist lots of blood and gore, ogres eating knights for snacks, and arms getting whacked off.

I ran across Beowulf again in college, in an English literature class my sophomore year. Being a mixed-gender class and something more serious than high school students thinking of graduation, we focused on the epic poem itself, its structure and narrative, its history and the various literary theories about it. (Am I something of a cretin to say the blood and gore approach was more engaging?)

In the 1980s, I was reading John Gardner’s fiction and discovered his short novel Grendel, telling the Beowulf story from Grendel’s point-of-view.

Years passed. Decades, actually. And then, in a New Orleans bookstore, while perusing the poetry section, I found a new translation of Beowulf by the Irish poet and Nobel Prize winner Seamus Heaney. Interest in Heaney and nostalgia for high school and college compelled me to buy it. It’s a fine translation, true to the form of epic poetry, and stirring to the heart, especially when read aloud.

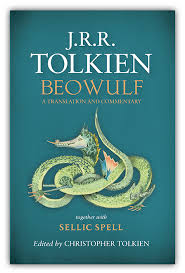

It’s been no secret that J.R.R. Tolkien had translated Beowulf. What has been rather secret is the translation itself. Tolkien scholars knew it was part of the author’s literary estate; Christopher Tolkien, son and literary executor, had discussed it. And now, more than 40 years after Tolkien’s death, the translation has been published.

And what a volume it is: a prose translation by J.R.R. Tolkien; notes and an extensive commentary by his son; a version of the Beowulf story by Tolkien, entitled “Sellic Spell”; and two poems written by Tolkien under the title of “The Lay of Beowulf.”

The best way to experience the translation, as poetic a prose as I’ve come across, is to read it. This is an excerpt of the arrival of Beowulf and his men in the land of the Ring-Danes, there to do battle with the ogre terrorizing the country:

“The street was paved in stone patterns; the path guided those men together. There shone corslet of war, hard, handlinked, bright ring of iron rang in their harness, as in their dread gear they went striding straight unto the hall. Weary of the sea they set their tall shields, bucklers wondrous hard, against the wall of the house, and sat then on the bench. Corslets rang, war-harness of men. Their spears stood piled together, seaman’s gear, ash-hafted, grey-tipped with steel. Well furnished with weapons was the iron-mailed company.”

I still feel the DNA of the high school experience with warriors, blood and gore.

J.R.R. Tolkien

What was new to me was “Sellic Spell, ” Tolkien’s telling of a version of the story (the hero’s name in this one is Beewulf, not Beowulf). The story has the air of playfulness around it; it’s not exactly a send-up but perhaps a more contemporary interpretation. I was reminded of Tolkien’s Christmas letters he wrote to his children for a number of years, when they were still young enough to be enraptured by the magic. The letters were published in 1976 as The Father Christmas Letters, and the polar bear is still one of my favorite story characters.

Reading this prose translation of the Beowulf story is also a reminder of how much the epic and other Norse tales influenced The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Beowulf includes all the familiar elements we know from Tolkien’s stories and Peter Jackson’s movies—a quest, a monster needing to be tamed, swords with powers and names, heroism and courage, and the battle between good and evil.

Image by familymwr. Sourced via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and the recently published Poetry at Work (T. S. Poetry Press).

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Boris Dralyuk and “My Hollywood” - September 9, 2025

Martha Orlando says

I’ve always loved Tolkien! Now, I need to get this book so I can read his translation of Beowulf. Blessings, Glynn!

Marcy says

Great writing Glynn, you told this so well. My memory takes me back when I was in my late forties, working in the High School Library. Paperbacks of “Beowulf” down in the fiction room with that awful hairy animal on the front. Required reading for the English Department as one by one students checked them out. Rather slim book I remember, four of my older grandsons have read it but I didn’t. After what you said about the book seems like one I might like to read. Good job.

Megan Willome says

When I read Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf a few years ago, my first thought was, “Tolkien totally ripped off Beowulf for LOTR!”

Monica Sharman says

I read Seamus Heaney’s aloud to my son. Really enjoyed it (which feels funny to say, considering all the blood and gore). Thanks for letting us know about this one. I look forward to the “Sellic Spell” part.

Marjorie Maddox says

I always love to hear these “first encounters.” Thank you.