My childhood was 1950s and 1960s New Orleans, during the last hurrah of segregation. I often rode the buses with my mother, who hated to drive into the city, and I learned which section of the bus we were to sit in. The suburban movie theaters, smaller versions of the big palaces on Canal Street, had two segregated sections—downstairs and the balcony. If I needed a drink of water when I accompanied my mother to the A&P supermarket, I was directed to the water fountain designated “white.”

Children, especially Southern children, didn’t question their parents. For me, the questioning didn’t happen until I was 14, preparing to enter high school. The schools in our New Orleans suburb had integrated the year before, with enough violence to require the daily presence of federal marshals and local police. My parents began to search for every option imaginable to avoid sending me to the public high school. I finally told them no. I was going to the public high school, regardless of what concerns they had.

Everything was changing in the 1960s, but the seeds of change were planted long before. One of those seeds was the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, an explosion of African-American culture centered in New York and embracing literature, music, theater, painting, and more. Associated with the renaissance were names like Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, W.E. B. Du Bois, and Langston Hughes. It was an amazing period in African-American cultural history, and an amazing period for African-American poets and poems. One of the beneficiaries of the period was poet Gwendolyn Brooks.

Almost 40 years after the renaissance, Brooks (1917-2000) wrote this poem about Langston Hughes:

is merry glory.

Is salutatory.

Yet grips his right of twisting free.

Has a long reach,

Strong speech,

Remedial fears.

Muscular tears.

Holds horticulture

In the eye of the vulture

Inform profession.

In the compression—

In mud and blood and sudden death—

In the breath

Of the holocaust he

Is helmsman, hatchet, headlight.

See

One restless in the exotic time! and ever,

Till the air is cured of its fever.

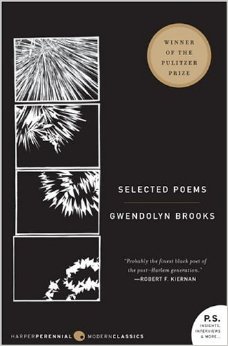

She published numerous books of poetry, including Selected Poems (1963). It includes poems from previous collections, a few new poems, two essays about her, and an interview with her by Studs Terkel. It’s a classic introduction to Brooks and her poetry.

The poems are simple, sometimes deceptively so. Many of them are rhyming poems. All of them reflect the love of people, the people she grew up with and knew, many of whom are what even then would have been called the urban poor. She captures their dignity and their faith, and their fundamental humanity.

The Bean Eaters (1960)

They eat beans mostly, this old yellow pair.

Dinner is a casual affair.

Plain chipware on a plain and creaking wood,

Tin flatware.

Two who are Mostly Good.

Two who have lived their day,

But keep on putting on their clothes

And putting things away.

And remembering . . .

Remembering, with twinklings and twinges,

As they lean over the beans in their rented back room that

is full of beads and receipts and dolls and cloths,

tobacco crumbs, vases and fringes.

Brooks’ poetry changed in the 1960s, reflecting civil rights struggles and the violence often inflicted upon those fighting for it. But it never lost something basic in her poems—the realization that history is not something confined to the past. History is also the present; what happened 100 years ago, 50 years and 20 years ago is in a very real sense still happening today, and still shaping who we are. We don’t really escape the past.

This doesn’t have only negative implications. The good things from the past—the grandmother who loved us, the elderly aunt who would invite us to visit for a week, the uncle who pressed good novels on us to read, those “bean eaters” we knew—continue to shape us as well. We may not be able to go home again, as author Thomas Wolfe said, but home and the past are always with us.

That’s the real lesson of Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetry.

Image by flattop341. Sourced via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and the just-published Poetry at Work (T. S. Poetry Press).

__________________

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Martha Orlando says

Amazing review of one amazing poet. Thanks for this introduction to Gwendolyn Brooks!

Maureen Doallas says

Good to see this post during African American History Month.

More people should discover Brooks.

nance.mdr says

i like this poem

Diana Trautwein says

What a find. Thank you. I remember studying the Harlem Renaissance, but i don’t remember a female poet being mentioned. Grateful you’ve brought her to the fore here.

Robbie Pruitt says

Love the Langston Hughes poem!

SimplyDarlene says

I learn so, so much here.

Thanks, Professor Poetry. 😉

BTW, the last 2 lines of the Bean Eater – wow. Snap! Pop! Changed the mental imagery I had going on… I could smell the poem at that point too.

Blessings.

Megan Willome says

I love Gwendolyn Brooks! Even though she is from a different time, her poems speak to the mom in me like few other poets do. She has an amazing mixture of humor and pathos.