There was poetry at work over about 25 years in the 19th century, as three events helped create the Christmas holiday celebration we know today. One was Charles Dickens and his series of Christmas stories, beginning with A Christmas Carol. Second was Queen Victoria’s embrace of the Christmas tree as a holiday tradition. But before both of those, and across the Atlantic, was a poem.

In 1822, Clement Moore, the son of a clergyman and soon to become a professor at a theological seminary, wrote a poem for his children. And he recited it to them. Word spread, and the following year “A Visit from St. Nicholas” was published in a newspaper. We know it better by its first line, “’Twas the night before Christmas.” The poem became widely known and included in anthologies, volumes of poetry, holiday publications, and newspaper articles. Various versions of the poem have been produced over the years; a popular one for those of us born and raised in New Orleans and south Louisiana is The Cajun Night Before Christmas which my family can still convince me to read aloud, complete with Cajun accent, which I don’t have but can imitate fairly well (I will admit to being one-fourth Cajun from a genetic perspective).

Moore died in 1863 at his home in Rhode Island. He might be amused to know that contemporary grinches have undertaken to prove that others actually wrote the poem, that he was too religious to have such a jolly view of Christmas, and that the only thing that saved his personality was having children.

To all of which I say, “Bah, humbug!”

I like how Moore describes the work of St. Nicholas, and it tells us much about the work of Christmas then and the work of Christmas today.

Second, St. Nicholas is noisy. He and his miniature sleigh and reindeer may be small, but they are loud. They arrive with a clatter, noisy enough to wake everyone except the children.

Third, he’s fast, or as Moore says, “lively and quick.” I suppose it’s a requirement of the job. Think of all the homes that have to be visited.

Fourth, he knows his work team by name. He refers to each of them individually and personally, especially since he’s giving them instructions on how to land on the roof. (The noise continues, of course, on the roof with all that prancing and dancing and stomping.)

Sixth, he is no role model. He puffs away at his pipe, not realizing that most workplaces today have banned indoor smoking. (The 1820s must have been a more lenient time.)

Seventh, he may be shouting at reindeer outside, but inside St. Nicholas works silently and quickly. His work is over and done with in a flash.

Eighth, he leaves the same way he came—the chimney. That’s twice he faces hazardous conditions on the job.

Ninth, he leaves with a sense of style and panache, exclaiming to all within hearing to have a good night and a happy Christmas. (Today he would be legally required to say “Happy Holiday” or “Enjoy your WinterFest.”)

Tenth, work in the 1820s, even the work of Christmas, was harder. We’d never allow airplane pilots today to work those kinds of hours.

Simpler, yes. Harder, yes. But the heart of the work—the excitement of Christmas—is still very much with us.

A Visit from St. Nicholas

By Clement Clarke Moore

’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds;

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads;

And mamma in her ’kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a long winter’s nap,

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from my bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash.

The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow,

Gave a lustre of midday to objects below,

When what to my wondering eyes did appear,

But a miniature sleigh and eight tiny rein-deer,

With a little old driver so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment he must be St. Nick.

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name:

“Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now Prancer and Vixen!

On, Comet! on, Cupid! on, Donder and Blixen!

To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

As leaves that before the wild hurricane fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky;

So up to the housetop the coursers they flew

With the sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too—

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof

The prancing and pawing of each little hoof.

As I drew in my head, and was turning around,

Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound.

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a peddler just opening his pack.

His eyes—how they twinkled! his dimples, how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard on his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke, it encircled his head like a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little round belly

That shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his head

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose;

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle.

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight—

“Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night!”

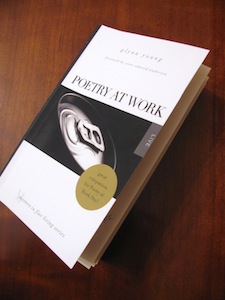

Image by filtran. Sourced via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and the just-published Poetry at Work (T. S. Poetry Press).

Buy the book Poetry at Work

Celebrate Poetry at Work Day

_____________________________

Visit the official Poetry at Work Day poster page for free printable posters and computer wallpapers

_____________________________

Poetry at Work, by Glynn Young, foreword by Scott Edward Anderson

“This book is elemental.”

—Dave Malone

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

- Robert Waldron Imagines the Creation of “The Hound of Heaven” - April 8, 2025

Maureen Doallas says

Fun post, Glynn.

All those cookies and glasses of milk do his waistline no good, sending up the cost of those health insurance premiums. And oh, the stress of getting elves to obey!

Merry Christmas to you and yours. Thank you for all the wonderful posts throughout the year!

Jody Lee Collins says

Glynn, I had the joy of reading this to some second graders last week when I was subbing at school. We had a bit of a conversation about ‘mom in her kerchief and I in my cap.’ My, my,how things have changed.

🙂

Glynn says

There was a point to wearing “kerchiefs and caps” to bed — it helped keep people warm in the days when fireplaces furnished the heat for the house.

Thanks for the comment!

Marcy Terwilliger says

Yet, the saddest part of all is when the child finds out one day that old Santa was not for real. Some big mouth kid spilled the beans & took away the dream along with Peter Pan. So you try to explain it’s the Spirit of Believing in something more than a man in red. It’s a day of the birth of the Christ child, gifts exchanged out of love for man. Going to Christmas Eve Service & lighting candles in the dark. As I watch my last grandchild at six who still believes in Santa Claus & wish they always did. Just like in all things they grow & change, nothing stays the same, but if I could still sew a shadow on their backs I would & let them remain Peter Pans.

Glynn says

I was in first grade when our modern teacher informed the class that Santa Claus did not exist. Thirty distraught children went home that day, and the parents of 30 distraught children called the principal.

Thanks for the comment.