My introduction to Ted Hughes was, for better or worse, a rather bad one.

When I was in college, the poems of Sylvia Plath were all the rage. She was known as the poet who had killed herself (1962) by sticking her head in a gas oven, and it was that ghastly tragedy that seemed to provide the initial attraction. These years were also the first full rush of the feminist movement, and Plath became a symbol—the poet who had killed herself because her husband had left her for another woman.

I’m not sure if this is the stuff of poetry or soap opera, but for years Hughes was called “murderer” at public readings.

In between came greater acclaim, numerous books of poetry that became bestsellers, and being named England’s poet laureate in 1984, a position he held until his death in 1998.

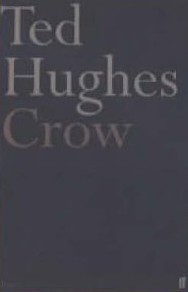

In 1970, the year of his third and lasting marriage, Hughes published Crow, a collection of rather extraordinary poems that represented both a significant turn from his previous work and helped establish him as one of the leading poetic voices of the 20th century.

A reading of Crow is an immersion into a new mythology and creation myth, with the subject of creation being a creature called Crow. But it is a mythology that hearkens to the account of creation in Genesis, Jesus in the New Testament, Greek mythology, Homer’s The Odyssey, and even Beowulf. The reader also can’t help thinking of Poe’s The Raven, another great work of dark imagination involving a creature associated with death. Crow is a dark work filled with despair, and yet containing a spark of hope, almost in spite of itself.

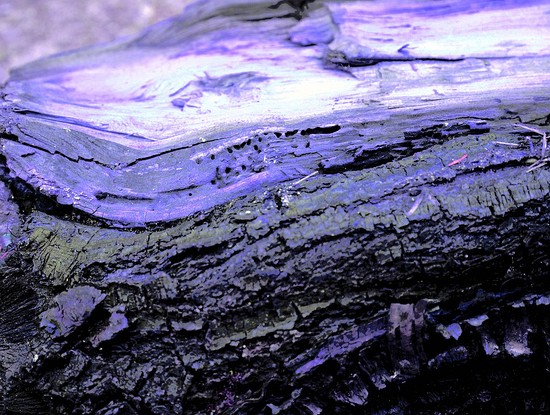

The connection to creation myths occur repeatedly throughout the collection. Crow begins as colored white, attempts to battle the sun and survives, yet comes away from the conflict scorched black. Sometime after various other adventures, we encounter “Crow Blacker Than Ever, ” which repeats the creation myth (and recalls the first and second chapters of the book of Genesis):

Crow Blacker Than Ever

When God, disgusted with man,

Turned towards heaven,

And man, disgusted with God,

Turned towards Eve,

Things looked like falling apart.

But Crow Crow

Crow nailed them together,

Nailing Heaven and earth together-

So man cried, but with God’s voice.

And God bled, but with man’s blood.

Then heaven and earth creaked at the joint

Which became gangrenous and stank-

A horror beyond redemption.

The agony did not diminish.

Man could not be man nor God God.

The agony

Grew.

Crow

Grinned

Crying: “This is my Creation, ”

Flying the black flag of himself.

—Ted Hughes

Throughout the poems, no matter what the circumstances described, Crow remains resilient, perhaps much like Hughes himself. Some have speculated that the work was a way for Hughes to bring resolution to two failed marriages and his wives’ suicides.

Regardless of what inspired Crow, it remains a significant work in Hughes’ development as a poet, and in 20th century poetry generally.

Related:

- A succinct summary of Crow and its importance in Ted Hughes’ career, by The Ted Hughes Society.

- Recording of Hughes reading selections from Crow.

- Hughes’ biography at The Poetry Foundation.

- In June 1970, Hughes recorded an interview on the writing of Crow.

Image by Wonderlane. Sourced via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and the forthcoming Poetry at Work(T. S. Poetry Press).

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Mary Brown and “Call It Mist” - September 18, 2025

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

Maureen Doallas says

Hughes is more than a force in his own right, all the drama of his personal life aside. ‘Crow’ is magnificent, I think.

I have a copy (one of only 250) of the Gehenna Press edition of Hughes’s ‘A Primer of Birds’ with woodcuts by Leonard Baskin, signed by both. It’s rather delicate now. Baskin and Hughes collaborated often; their work together was phenomenal. I collected Baskin’s works on paper when I could and am proud to own a number of books from Gehenna Press, which Baskin founded. I was privileged to meet Baskin whose erudition was astonishing.

nance.mdr says

i think i’ll stick with my electric oven…

um.... says

i dont get this