Today, Poets and Poems considers a book by Christopher Reid: A Scattering.

You reach a certain age and find yourself thinking more about a subject you rarely consider when you’re young—death, of yourself, your spouse, your parents, your friends. It becomes a topic of conversation, and you find yourself doing regularly what used to make you smile about your parents—reading the obituaries.

When you’re 19 and immortal, this consideration of death may seem slightly bizarre. When you’re older and something less than immortal, you understand death is part of life. But sometimes it arrives out of cycle—a child, a friend, a spouse. Sometimes death comes too soon, as it did for British poet Christopher Reid.

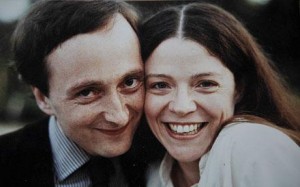

In 2005, Reid’s wife, actress Lucinda Gane, died from cancer. She was 57. For Reid, abstract understandings of what cancer is and what it can do became all too real. He watches his wife of 30+ years grow progressively worse. Cancer and illness have moved beyond the intellectual to the emotional and personal; they become something shared that must be lived through.

Reid wrote a series of poems, A Scattering, about his wife’s illness, death and aftermath, and he wrote them for the reason any writer would—to make sense of what was happening. When sense couldn’t be made, the poem became a way and a means to acceptance. What is clear is that death isn’t the end point; death never is. Instead, it becomes simultaneously both a mid-point and a beginning, leading to a different life for the survivors, a life already hinted at in the moment of death. Consider this untitled poem:

1

Sparse breaths, then none —

and it was done.

Listening and hugging hard,

between mouthings

of sweet next-to-nothings

into her ear —

pillow-talk-cum-prayer —

I never heard

the precise cadence

into silence

that argued the end.

Yet I knew it had happened.

Ultimate calm.

Gingerly, as if

loth to disturb it,

I released my arm

from its stiff vigil athwart

that embattled heart

and raised and righted myself,

the better to observe it.

Kisses followed,

to mouth, cheeks, eyelids, forehead,

and a rigmarole

of unheard farewell

kept up as far

as the click of the door.

After six months, or more,

I observe it still.

What Reid knows and expresses in these poems is this: you don’t “survive” the death of a beloved spouse; you change. And what follows continues to be shaped by the one you’ve lost and the love you’ve shared.

Reid is the author of some 15 collections of poetry, two children’s books, and five collections and anthologies (he served as editor of the collected letters of poet Ted Hughes). A Scattering received the Costa Book Award for best poetry book of the year in 2009 and best overall book of the year (Reid was the first poet since Seamus Heaney to take the overall award).

Honest and often pointed, the poems of A Scattering read true. They were born in loss, a loss that seems almost unimaginable, but they honor that loss and the person who was there before.

Image by mycatkins. Sourced via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and the forthcoming Poetry at Work (T. S. Poetry Press).

___________________________

Click to get 5-Prompt Mini-Series

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Katie Kalisz and “Flu Season” - April 15, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Michelle Ortega and “When You Ask Me, Why Paris?” - April 10, 2025

nance.mdr says

so good to want to get out of bed…

Glynn says

Some days,

getting out

of bed can be

an achievement.

Nancy – thanks for reading and commenting.

Maureen Doallas says

“Not about stages at all” could not be more true, and I say that as one who has lost a sibling, grandfather, and aunts and too many friends to the worst kinds of cancer.

Reid’s poem quoted here speaks to so much. That opening line stuns, the way death does. And I love his insertion of “a rigmarole / of unheard farewell”: marvelous.

Glynn says

The poems are beautiful, Maureen. You read them like he’s distilled the love he felt for his wife into each word.

As for stages, no one told me to expect to begin grieving for my own father three years after his death. It’s when I learned that death, like life, is very much an individual thing, and we can’t simply reduce it to some common denominator.

Thanks for the comment.

Robert Bathurst says

A Scattering will be performed as part of a double bill of Christopher Reid poems at the Minerva Theatre, Chichester, Jan 22-31

http://www.cft.org.uk/5218/LOVE-LOSS-AND-CHIANTI/757