A few years ago, I was asked to train a mixed group of a dozen or so new staff in an expanding claim office. About half were experienced adjusters hired from other insurance companies. Skilled negotiators and problem solvers, they needed only to learn the company’s IT systems and procedures.

The rest were promotions from within the company’s own “fast track” unit, handling straightforward fender benders. They were masters of procedures and technology, but needed to learn the nuances of coverage, liability and valuing things with no price tags, like arms and legs, time and companionship.

Throughout the week, I felt crushed by the fortress of the Claims Procedural Manual that hemmed in these young upstarts. They succeeded on the conveyor belt of claim handling because they steadfastly followed a scripted code of “if-then.” Within precisely metered scenarios, they knew exactly when to say yes and when to say no. They could rattle off the approved vendors for any city in the nation. The multiplier to depreciate a Toyota’s headlight sat ready at the tip of their tightly lashed tongues.

But they couldn’t stray from the prescription even when following it would prove disastrous. Loosed from their strict robotic tethers, they froze at the one thing a successful adjuster (or a successful anyone, for that matter) must be able to do: the right thing at the right time for the right reasons. As Anne Sexton wrote,

But suicides have a special language

Like carpenters they want to know which tools

They never ask why build.

They’d been squeezed through management’s portal of rigid procedures until the core claims principle — Pay what we owe: not a penny more, not a penny less — was less an undergirding philosophy than an exact dollar amount calculated by simple algebra.

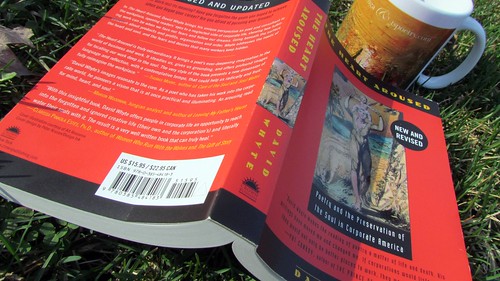

In the final chapters of The Heart Aroused, David Whyte follows Coleridge’s haunting vision of a flock of starlings in our unending quest for order amid chaos.

The starlings drove along like smoke . . . misty . . . without volition — now a circular area inclined in an arc — now a globe, now . . . a complete orb into an ellipse . . . and still it expands and condenses, some moments glimmering and shivering, dim and shadowy, now thickening, deepening, blackening! (p. 216)

According to Whyte, the flock, “a powerful personality without a solid identity, ” might describe the modern corporate workplace, always shifting and changing in the face of volatile markets, continuous improvement, and breakneck technology. Our kneejerk response to the chaos may be to yank and stretch it into clean linear order. But he calls us instead to embrace the vital intertwining of chaos and order, and more, to live in the boundary waters flowing between the two.

Computer modeling shows that scenes such as Coleridge’s glorious starlings do not appear from regulated efforts to “form a flock” but from accumulated individual action surging within a few simple parameters. This beautifully (un)orchestrated movement is the result of interrelated parts responding to the shifts of others.

Allowing the science of complexity — and the poetic tradition — to play out naturally in the maze of our cubicle floors is to “fold meaning into the simplest elements and allow complexity to emerge from their natural self-generation.”

Within our organizations, Whyte says, we strangle innovation and creativity, ordering complexity away through repressive rules and protocols.

It is astonishing to witness the human ability to . . . take on every possible kind of experience in an ordered, burdensome way, as if we could not countenance the possibility of standing upright for a single moment, freed from the extra weight of the structures we love to carry with us. A simple love for the purity of the piano becomes a schedule of lessons we can no longer fit into our schedule. A step toward a subject for which we have a passion becomes a costly exercise in college fees and course requirements . . .” (p. 254)

Whyte wants me to believe my trainees were not “herbivorous animals about to stampede out of control unless you are constantly riding the herd.” Given a clear set of boundaries coupled with freedom to adapt and imagine, perhaps they could look like a spectacular flock of starlings on the move. Wordsworth wrote,

There is a dark invisible workmanship

that reconciles discordant elements

and makes them move in one society.

I almost get the idea he wants us to trust folks.

_____

Is such trust reasonable? Is it even possible? What do you think? We conclude our discussion of The Heart Aroused: Poetry and the Preservation of the Soul today. Our new book club begins April 4th, featuring Rumors of Water: Thoughts on Creativity & Writing. Come along?

Photo by Sandra Heska King. Used with permission. Post by Will Willingham

___________

Buy a year of Every Day Poems, just $5.99— Read a poem a day, become a better poet.

- Earth Song Poem Featured on The Slowdown!—Birds in Home Depot - February 7, 2023

- The Rapping in the Attic—Happy Holidays Fun Video! - December 21, 2022

- Video: Earth Song: A Nature Poems Experience—Enchanting! - December 6, 2022

Megan Willome says

You’re so good.

As an editor, part of my job is to trust my writers, but to wisely oversee them. I want them to sound like themselves, but with proper punctuation that fits within our magazine’s style. A lot of what I do is subjective (as is your job), yet also within a framework (for me, AP Stylebook; for you, some insurance code).

Will Willingham says

You help people sound like themselves. I just keep saying that over and over to myself.

What kind of gift is that, that you get to give?

Trusting people with the subjective is very hard. Misapplied, rules give us something to squeeze them back into and give us a sense of control again. But I like how you put yours to work. To help people sound like themselves, within the given parameters.

L. L. Barkat says

And that’s exactly what you were up against—a code that had taken over the voices of the employees. It really is hard to be a person who knows how to work creatively within a basic framework.

Hmmm. Maybe that’s why I like to make my own frameworks. More room to talk (oh I do love to chat 🙂

Maureen Doallas says

I imagine the impression

that’s made once

a line is concluded.

Will Willingham says

You know, some industries are just not the place where one finds groundswells of creativity. I’m starting to believe that perhaps there’s a way to introduce it into mine. David Whyte is filling my head with subversive thoughts. 🙂

Glynn says

My contribution is here: http://faithfictionfriends.blogspot.com/2012/03/coleridges-starlings.html. I’ll have a final post tomorrow. This has been a great discussion – thanks for leading it.

Charity Singleton says

I find this principle of trust to be lacking considerably at my workplace. All too often, we create a rigid guideline because we don’t want to give room for employees to make judgments. And yet, when there is an opportunity to make a judgment call and they miss we are upset. Trust almost seems out of place in such a corporate culture, and yet the result is the very chaos we seek to avoid.

This book is so thought provoking, and the way you bring these chapters to life, just wonderful.

Glynn says

My final post on the book: http://faithfictionfriends.blogspot.com/2012/03/strange-and-familiar.html

Will Willingham says

Charity, I think it’s a pretty huge thing. Every manager I’ve ever had that has actually communicated trust to me has gotten nothing short of the best I have to offer. But keep imposing new rules, and tying them tighter, and I will do the least amount required to stay in the lines. I think trust has to be one of our most powerful our most powerful gifts.

Kimberlee Conway Ireton says

TS and Co., Thank you for the conversation around this book. Such a privilege to eavesdrop and feel inspired by your words–inspired to read the book (someday) but more, inspired to live creatively within the constraints of my own (very non-corporate) life.

Donna Falcone says

I’m piping up (butting in) here, addmittedly having not read the book, but I peeked in anyway.

LW, I love this.