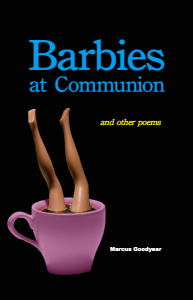

Welcome to Barbies at Communion: and other poems. And welcome to Marcus Goodyear.

Marcus is the Senior Editor for Foundations for Laity Renewal, which was founded by the H.E. Butt Foundation to “renew society by renewing the church.” You find most of his editing and writing work at The High Calling, The High Calling Blogs and Christianity Today’s Faith in the Workplace. He also blogs at Good Word Editing.

And you find it in his poems.

I won’t be coy. I loved Barbies at Communion. It’s about the daily, ordinary things (the super-collifer notwithstanding), and it’s because Marcus sees the poetry in the daily, ordinary things.

So Marcus took some time to talk on the phone and through email, to answer some questions I had. And he graciously responded, providing more details and insights into his own work and poetry in general.

Read the interview, and then click here to the post on my blog for an opportunity to receive a free copy of Barbies at Communion.

I have to know about the origin of the super-collider poem. And what your wife thought of it as a Mother’s Day poem.

Oh yeah, the super-collider poem. I’ve always had an amateur’s fascination with science and quantum physics. (In high school I won the state science fair in Mathematics, oddly enough.) Anyway. These days, my interest in science is limited to Nova, science fiction, and science magazines. That poem was inspired in part by an article in Technology Review from MIT.

My wife liked it, I think. It’s not really romantic, but it is kind of fun. Mother’s Day isn’t about romance, anyway. Besides. She’s used to me writing weird poems for her. One Valentine’s Day, I wrote her a sonnet about gecko toes and the van der waals force. Another time, I wrote her one about zombies. Thankfully, she tolerates my weirdness.

Where did you find a love for poetry? It’s not a “typical” (I almost said “normal”) thing these days.

About 10 years ago I was teaching high school English by day and attending grad school at night. I remember struggling through Keats’ poem “Lamia” over my lunch break one day. I had to write a two-page paper about this poem for class that evening, and I couldn’t figure out what it was about. I couldn’t find the answer

Then something just clicked. The poem didn’t have an answer. It was just an elaborate word game (about a snake woman). I still like Keats to this day, though I prefer other poems of his like the “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” His letters are cool, too.

How did you come to write poetry?

I had to teach students to read it. To make that more fun, I perversely decided that the students should try to write some too. It was really a tricky way to get them thinking about rhetorical techniques.

Through all of the crazy assignments–from the Ekphrasis poem to the N+7 poems to the traditional haikus–I had a policy that I would never assign something that I couldn’t do myself. Most of the time, this meant that I completed all of the assignments that I asked my students to complete. Sometimes, I would let them grade me. It was very scary. High school students don’t lie.

I love that poem. The city has grown, of course, but it still has the same heart. It still has the same complexity. Whitman’s poem anticipates change, and embraces it. In that poem–and people should just go read it out loud to themselves–he talks about being alive in New York. That still applies.

He talks about New York being filled with people. That still applies. And the river flowing around Manhattan. That still flows.

He says, I lived here. I walked here. I rode a ferry over these waters. I swam in them. All of the changes that have happened since Whitman’s New York are superficial when compared to the one constant. People are still resolutely human.

Someday, I hope to go back to Brooklyn Bridge and read the poem aloud again while people walk by and cars drive underneath me and the boats sail underneath them. I love that poem.

The title poem for Barbies at Communion is about your daughter playing with her dolls during a church service. How did you make the connection from that to the poem? What was the spark (assuming there was one)?

For me a poem is somewhere between image and argument and story and metaphor. Sometimes I have trouble letting go of an image that has bothered me–like the image of communion with those naked dolls. As a father, I felt anxiety about my daughter in that instance. Was it okay for her to be a kid during communion? Was it okay for the naked dolls to be, well, naked? Did it bother anyone else around us? Should it bother me as much as it did?

All of that anxiety needed an outlet. The poem doesn’t really answer the problem except to embrace my daughter’s innocence. She doesn’t care about propriety because she doesn’t understand what it means to be naked. Neither did Eve before the fall. And what is Communion except a chance to reconnect with God, to find our own innocence again through the grace and sacrifice of Jesus?

So the spark, in a literal sense, was the event itself. There were Barbies at communion on Sunday, and I didn’t know what to do with them. The poem helped me think it through.

The poems in Barbies are about the stuff of everyday life – children playing, mowing the grass (even if it’s dead), stuff stored in the attic. This isn’t the poetry of academia, which seems to dominate (some might say stifle) contemporary poetry. What is it about the everyday that appeals to you?

It’s where I live! I need my life to have meaning today, not next year, not 10 years from now, not in retrospect while I’m breathing my last. If I can’t find God in the ordinary places of life, either I’m not looking hard enough or he’s not nearly as approachable as I need him to be.

This is a paradox too. God appears in all the ordinary places, burning bushes, naked Barbies, plumbing disasters. But when he does, those places become holy. Moses had to take his shoes off. That’s one reason why the formal-ness of poetry seems fitting to these images. Poetry is very formal. It’s a way of taking my shoes off and showing respect to God when I catch glimpses of him.

I wouldn’t come down too hard on Academia. They do good work. They have a lot of pressures. They need publication credits. They need to fill their journals with names that will make them look impressive. Like any profession, it’s a community of its own, with rules and relationships and networking. As someone writing poetry outside of Academia, I can feel like I’m not part of that community, but that’s really just a call to suck it up and send out more work (which I don’t do often enough because I don’t like rejection).

What I personally find so appealing about the poems of Barbies is the concrete language. Tell us a bit about your writing background – and when was it you decided you were a writer? And what’s your education background?

I was a foreign exchange student to Germany during high school, but I didn’t speak German. Pretty strange decision. I’m a talkative person, though, so I had all these words building up inside with no way to share them. That’s really when I started writing.

When I got back to the US, I took an Independent Study Mentorship under Max Lucado. He was the minister at my church, and he wasn’t quite the publishing force that he became. The youth minister ended up working with me most of the time, but it was transformational for me to have someone like Max say, “Yeah, you’re a writer.”

Now, do you really want to know where I went to school? I earned a BA in English from Texas A&M University and an MA in English from UTSA.

How did you come to Foundations for Laity Renewal?

It’s all in who you know. They were looking for an editor, so they contacted Max’s personal editor. She has been a long friend of my family and my wife’s family. She thought of me and gave me a call on President’s Day 2005. I don’t normally remember dates like that, but this one stuck. At the time, I was looking to move to a new school, change things up a bit in my job so I wouldn’t get stale. It seemed natural to cast the net a little wider and send an application to Laity Renewal. A few months later, we moved to Kerrville where Laity Renewal is headquartered.

Tell us a bit about what it is and what it does.

This sounds cheeky, but we really are all about laity renewal. That’s our primary philosophy–renewing individuals, so they can be agents of renewal in their families and workplaces, so those small groups can be agents of renewal in their communities.

We work toward this philosophical goal through various programs–youth camp, family camp, free camps, Laity Lodge retreat center, and of course the High Calling of Our Daily Work radio program and TheHighCalling.org (which includes HighCallingBlogs.com).

And how did poetry come to be one of the features at the High Calling Blogs?

Blame L.L. Barkat. She called me up one day and said, “I want to try this poetry thing.” I was a little nervous about it, and remember saying, “Nobody cares about poetry.” It’s all part of this self-loathing problem I have. But L.L. can be very convincing. She got me to agree to a test period, and it’s been very helpful in building community.

In some ways, poetry has been historically important to Laity Renewal. When you come out to Laity Lodge in the Fall, Glynn, you’ll see poetry everywhere, hidden on bathroom tiles, on stones in the fountain, on placards in the garden, carved into beams in the ceiling. Poetry is really part of the architecture of the place.

So – what’s next? Another book of poetry? Or other things you’re working on?

I just keep writing poems and stories. I’ve got ideas for another novel. I’m querying some secular agents. And I’m working with you and L. L. on the game at TweetSpeakPoetry.com. I have a lot of high hopes for that project.

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

nance nAncY nanc hey-you davis-baby says

i enjoyed this post, glynn.

it was fun getting to know marcus a little bit better.

thanks.

L.L. Barkat says

Makes me proud to know Marcus. So smart, so fun. And besides, he blamed me for a good thing. 🙂

Kelle Sauer says

oh – so much new stuff about Marcus here! great interview!

laura says

And you that shall cross from shore to shore years hence, are more to me,

and more in my meditations, than you might suppose.

Thanks for suggesting it. Moments well-spent, reading this aloud, to myself.

Maureen Doallas says

I want Marcus to tackle Fibonnaci poetry next.

Good interview!

Cheryl Smith says

I love how you used the time in Germany to refine the gift within you. And thankful, for by extension, many are enriched, as a result.

Marcus Goodyear says

Goodness, these comments are such a gift. Thanks everyone. Thanks, Glynn for asking the questions. Thanks, Laura for some of my favorite lines from Whitman. Thanks, LL for encouraging me in this direction. Thanks, Maureen for the lead on a new form (I’m heading to investigate that now). Thanks, nancy and Kelly and Cheryl for the kind words.

I wish you all could be with me today at Laity Lodge for the poetry workshop this afternoon. We’re talking about personification, metaphor, and tone. Which actually sounds kind of boring, but it isn’t.

Kathleen says

The poetry you took a chance on promoting came at a time when (as Stevie Smith says) I was drowning not waving….and only poetry and you, and you, and you ~ knew. [curtsy to all you first responders] I’m breathing again, alive with words. The word was made flesh has a new fresh meaning now. Poema. Workmanship.