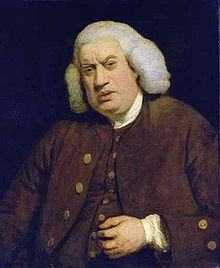

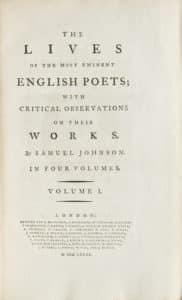

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), the great lexicographer, wrote three great works that influenced English language and literature even to our own day. The Dictionary of the English Language (1755) served as the pre-eminent English dictionary through the 19th century. The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765) gathered together and identified all of the plays of Shakespeare into one authoritative edition. And The Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets (1779-81) was the authority on the nation’s poets in the period up to the end of the 18th century.

That work on the English poets was one bookend of Johnson’s professional life. I found the other bookend, the one from the beginning, while on a visit to the Samuel Johnson House in London.

Samuel Johnson

Like many writers and poets who came to London in the early 17th century to make a living, Johnson wrote for literary journals, freelanced wherever he could, and generally scrabbled by while he looked for success. His first success was actually published anonymously—a long poem entitled “London (1738), ” based on the Third Satire by the Roman poet Juvenal.

The poem’s author soon became known, but the poem by itself wasn’t sufficient to launch and grow a career. Johnson would leave London for a time to work as a schoolmaster before returning to write the book that truly made his name. And it was a rather surprising book.

Richard Savage

Richard Savage (1697 or 1698 – 1743) was a poet who claimed to be the illegitimate son of an earl and a titled lady. There’s some support for the claim, although nothing really definitive. He made his name through a series of poems, including one entitled “The Bastard” that was aimed at embarrassing and humiliating his mother (which it did) and gaining him some hush money in the form of a pension (which it also did). In 1727, Savage was arrested with several friends and tried for the murder of a man in a coffeehouse which doubled as a brothel. Savage was found guilty but a few weeks later was pardoned by the king. His notoriety gained him access to all kinds of circles, both literary and aristocratic.

Savage was one of the first people Samuel Johnson met when Johnson arrived in London in 1737. They made an odd pair of friends, the older and rather refined-looking Savage and the younger and physically ungainly Johnson. For almost two years, they spent considerable time together, especially walking London’s residential squares late at night. During those walks Savage would describe his life, his parentage, his poetry, his passions, and his prejudices. When Johnson published “London, ” some believed (and some academics still do) that the main character in the narrative poem was a thinly disguised Savage. Johnson later denied it, but the question remains. Certainly Savage was an influence on the poem.

Savage eventually fell on hard times, left London (aided by friends like Alexander Pope) for Wales, and died in 1743 in the Bristol jail, where he had been imprisoned for three years for non-payment of debts. Johnson was commissioned to write Savage’s biography.

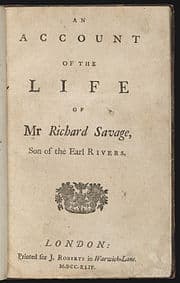

An Account of the Life of Mr Richard Savage

As described by Richard Holmes in Dr. Johnson and Mr. Savage, what Johnson created with this work was more than a standard biography. An Account of the Life of Richard Savage (1744) changed the nature of biographical writing, almost creating a new genre, something between biography and fiction. Johnson didn’t always get his facts right, but he wrote beautifully and entertainingly. Holmes also makes a good case for Johnson writing much of himself into the story of Savage.

Johnson’s biographer, James Boswell, was clearly uncomfortable with Johnson’s relationship with Savage and tended to downplay Savage’s influence. Savage was looked down upon for the rest of the 18th century. But his influence on Johnson was clearly there, whatever qualms Boswell might have had.

The Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets

The biography established Johnson. A year after its publication, he was commissioned to produce the dictionary. His growing reputation attracted a wide circle of admirers, and Johnson soon found himself part of the literary and social establishment.

I look at the dining table in the Johnson House, and can imagine David Garrick, Edmund Burke, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and others laughing, drinking, conversing and arguing. And I think of how much of what we know as the English language and English literature, including English poetry, moved through that room.

Related: Literary Tour: The Samuel Johnson House, London

Photo by zeze57, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Siân Killingsworth and “Hiraeth” - March 25, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Donna Hilbert and “Gravity” - March 20, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Emily Patterson and “So Much Tending Remains” - March 18, 2025

L. L. Barkat says

My eldest (Sara) loves the dictionary. I bought it for her, because it was one of those things that kept going back late to the library (and because she was so tickled by its originality and verve. 🙂 )

Interesting tale of Johnson’s life here!

Glynn says

I love Johnson’s definition of “pension:” Pension: An allowance made to any one without an equivalent. In England it is generally understood to mean pay given to a state hireling for treason to his country.

Of course, that didn’t stop Johnson from accepting a pension from King George III (yes, he who was king during the American Revolution).

Maureen says

Fascinating bit here, Glynn.

You are becoming our British lit expert.

Glynn says

Blimey!

Bethany R. says

This is an interesting bit of history I didn’t know. Thank you for writing and sharing it.

I wonder what his criteria was for deciding whether or not to include a word in his dictionary.

Glynn says

There are some 90,000 words in his dictionary. Some have straightforward definitions. Many are tongue in cheek,

Rick Maxson says

Now I’ll have to get my hands on his dictionary. This inspired me to look up some poems by Richard Savage. I’ve suggested an excerpt from “Nature in Perfection.”

Your posts from your visit to England are all very interesting, Glynn.

Glynn says

Rick, thanks for the comment. If I could afford it, I would live in London, at least for half the year. We even looked at small apartments, and even saw one of 150 square feet (think about that for a minute) in South Kensington (centrally located) that we could buy for about $900,000. We decided that occasional visits made more sense.

But it’s a wonderful city.

Rick Maxson says

Hmmmm. Slightly more than a 12 x 12 room for 900K. Visits are a much better idea. I tremble to imagine what a regular size house would cost. It’s like California housing on steroids.