Anita Miller, our guide on the Keats Walk, leads us from the Heath and back toward the town of Hampstead. We pass a small circus, with circus music and clowns smoking cigarettes behind the big tent. We make our way through the crowds to a narrow street called Keats Grove. About four houses down, we come upon Wentworth House.

The house was built in 1816, not long before poet John Keats first encountered it. As our guide and the docent at the house tell us, it was originally what we Americans call a duplex, with a wall dividing the house into two separate residences. The left side was occupied by Charles Armitage Brown, Keats’ good friend and hiking companion, and Keats himself after his brother Tom died in December 1818. On the right was the Dilke family, who moved out and were replaced by the Brawne family, including the eldest daughter, Frances, or Fanny, who became Keats’ great love and fiancée.

A meeting room on the left has been added in the recent past, suitable for lectures, poetry readings and other literary activities. Four rooms downstairs mirror four rooms upstairs, divided by the staircase, with the kitchen in the basement.

When Keats lived here, the house faced open fields leading up to Hampstead Heath. But building activity was already underway—Hampstead was too good a spot for builders to ignore for long. In the 18th century, it was a popular spot for spas and mineral waters, and thus the names of streets like Well Walk. That had mostly passed by the time Keats lived in the area.

From the outside, the house looks similar to what it did in 1819 and 1820. Keats actually lived here only a short time—from December of 1818 through May of 1819.

It is the place where he wrote some of his greatest poetry. Five of his six odes were written here, between mid-March and late May, 1819. So were both versions of “La belle dame sans merci.” There is a small tree in the front yard that occupies the space where stood the plum tree that supposedly inspired “Ode to a Nightingale.”

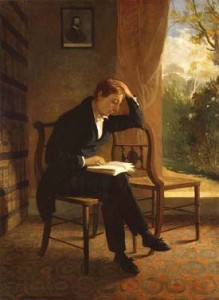

The two rooms where I spend the most time here are Keats’ study and the living room. The study is furnished largely as it was when he occupied it, including the pictures on the walls and the double chair (see painting). The living room is where he would lie on a sofa, incapacitated by consumption, facing the window and watching Fanny Brawne walking in the garden outside. Look closely enough and you can see both of them, separated by disease.

Living in the same house, Keats’ illness forced them to communicate mostly by letter. “You will have a pleasant walk today, ” he writes her in one letter. “I shall see you pass. I will follow you with my eyes over the Heath.” Keats offered to release Fanny from the engagement, but she refused. Indeed, after his death, Fanny would be in mourning for six years and remain unmarried for another six. It was only when she finally married that she removed his engagement ring.

As was common with the disease we know as tuberculosis, Keats would experience periods of rallying and improvement. He traveled to the Isle of Wight in the summer of 1819, he undertook various writing projects, he attended plays. He was even able to assemble the poems that became his third collection, published in June of 1820, which, according to his biographer Nicholas Roe, “…contains eight of the greatest poems in the English language, ” including The Eve of St. Agnes, Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, and Lamia.

After his death, Keats and his poetry nearly slipped into obscurity. Joseph Severn would paint his portrait several times in the ensuing years, but it would be Alfred, Lord Tennyson who revives interest in Keats and what he accomplished. And he changed poetry forever.

Our Keats Walk ends here at Wentworth House. Anita mentions that she has another walk, “Keats in the City, ” but we’ll have returned home before its next scheduled date. She’s also working on a Shelley walk to begin next July, and conducts walks on the Great Fire of London and Roman London. She’s been a wonderful guide. For a virtually non-stop two-and-a-half hours, we’ve walked with, looked for, and considered John Keats and his poetry.

We finally wander back toward Hampstead’s shopping district, looking for a late lunch. We find Anita sitting at an outside table at Café Dominique, and she highly recommends the food. We find ourselves a table.

Anita read it earlier in the walk, but it seems fitting to end our walk with his poem that seems to have predicted his end.

When I Have Fears that I May Cease to Be

Keats’ gravestone in Rome, via Wikimedia Commons

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain,

Before high-pilèd books, in charactery,

Hold like rich garners the full ripened grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starred face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour,

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

During November, we’ve been walking through the life and poetry of John Keats. This article concludes the series.

Photo by David Melchor Diaz, Creative Commons, via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and Poetry at Work.

A Month with Keats: Keats and Hampstead Heath

A Month with Keats: Poetry, Religion and Politics

A Month with Keats: A Walk into His Life

__________________________

“I require all our incoming poetry students—in the MFA I direct—to buy and read this book.”

—Jeanetta Calhoun Mish

- Poets and Poems: Sandra Marchetti and “Diorama” - April 24, 2025

- Poets and Poems: Christina Cook and “Roaming the Labyrinth” - April 22, 2025

- Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”: Creating a National Legend - April 17, 2025

Megan Willome says

This has been such a great series, Glynn! I hope you’re able to go back and do other tours and write about them for us.

Glynn says

Megan – thank you! And there will be some posts coming about a lecture at the British Library on T.S. Eliot, Samuel Johnson’s House, and the Charles Dickens Museum.