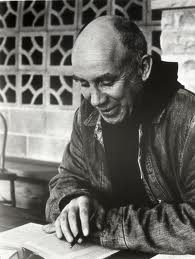

He died almost half a century ago, but Thomas Merton (1915-1968) continues to exert a significant pull on the imagination, the intellect, and the conscience.

Perhaps it is partially his resume: child of a New Zealand father and American mother; raised partially in France; parents dying of cancer; something of a dissolute youth related to his short stint at Cambridge; literary influences of Columbia University; conversion to Catholicism; joining the Trappist monks with their vows of silence at the Abbey of Gethsemani outside of Louisville, Kentucky.

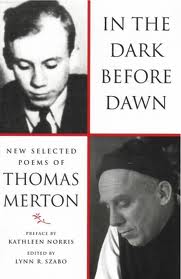

His poems have been collected and published over the years, but in 2005 Merton scholar Lynn Szabo of Trinity Western University in Vancouver assembled a broad array of his poetry in the volume In the Dark Before Dawn: New Selected Poems of Thomas Merton. The volume includes a preface by Kathleen Norris, herself a poet often compared to Merton and the author of Dakota: A Spiritual Geography and The Cloister Walk, among other works.

Rather than a chronological approach, Szabo has grouped the approximately 120 poems by themes: “Geography’s Landscapes, ” “Poems from the Monastery, ” “Poems of the Sacred, ” “Songs of Contemplation, ” “History’s Voices: Past and Present, ” “Engaging the World, ” “On Being Human, ” and “Merton and Other Languages.” Here is a poem, simply entitled “Song, ” from the section “Poems of the Sacred:”

The bottom of the sea has come

And builded in my noiseless room,

The fishes’ and the mermaids’ home,

Where it is most, most hell to be

Out of the heavy-hanging sea

And in the thin, thin changeable air

Or unroom sleep where some other where;

But play their coral violins

Where waters most lock music in:

The bottom of my room, the sea.

Full of voiceless curtaindeep

There mermaid somnambules come sleep

Where fluted half-lights show the way,

And there, there lost orchestras play

And down the many quarterlights come

To the dim mirth of my aquadrome:

The bottom of the sea, my room.

The poems in the collection are meditative and contemplative, reflecting Merton’s faith and how he applied it to everyday living as well as the larger issues of the day (one particularly arresting poem is “Original Child Bomb, ” a long poem focused on the dropping of the first atomic bomb). He also pays tributes to those literary influences, including a poem to Garcia Lorca but also to Hemingway, James Joyce, Rainer Maria Rilke, James Thurber, and Merton’s literary mentor at Columbia University, Mark Van Doren (who also influenced the Beat poets like Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac).

Merton’s influences extend across all of the disciplines he engaged, but especially so in poetry and faith. You read his poems, and you sense the dislocation of a life in the twentieth century (and that dislocation isn’t confined to that one century alone). And you sense how his found his center, and began to work outward to life.

His poems tell that story, and tell it well.

Related:

- The 2008 PBS documentary “Soul Searching, ” produced by Morgan Atkinson

- The Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Image by Kris Krug. Sourced via Flickr. Post by Glynn Young, author of the novels Dancing Priest and A Light Shining, and the recently published Poetry at Work (T. S. Poetry Press).

Want to brighten your morning coffee?

Subscribe to Every Day Poems and find some beauty in your inbox.

- Poets and Poems: Mary Brown and “Call It Mist” - September 18, 2025

- “Horace: Poet on a Volcano” by Peter Stothard - September 16, 2025

- Poets and Poems: The Three Collections of Pasquale Trozzolo - September 11, 2025

Maureen Doallas says

Merton had an extraordinary life, I think. His writings continue to be a deeply necessary philosophical source.

So much in “Song” strike me, especially his use of such words as “builded” and “unroom”; there is music in this verse and meaning profound.

Thank you for an excellent post, Glynn.

Megan Willome says

“And you sense how his found his center, and began to work outward to life.”–Beautiful.

in “Song,” I love the images of mermaids. Also the repetition of “the bottom of the sea,” used in different places and in different ways.

jerry says

When I get feeling shallow and world weary I look for Merton. His writings help me wade back into cool refreshing waters of the spirit. Thanks for sharing this Glynn.

Heather says

I just finished this volume as well. Beautiful.